Graphic novels—what are they really? Are they picture books for kids and childish adults, lighthearted comics, or a new approach to difficult topics for any audience? Could they be a whole new genre? And is that genre a form of literature? These questions are the subject of debate for literary critics, artists, and art historians from around the world.

At the library of the International school in Manila (the Philippines) that my children attend, each of the three halls of the library—for elementary, middle, and high schoolers, respectively—has an entire bookshelf intriguingly marked “graphic novels.”

What are the offerings on the shelf for elementary schoolers (grades 1-4 at our school)?

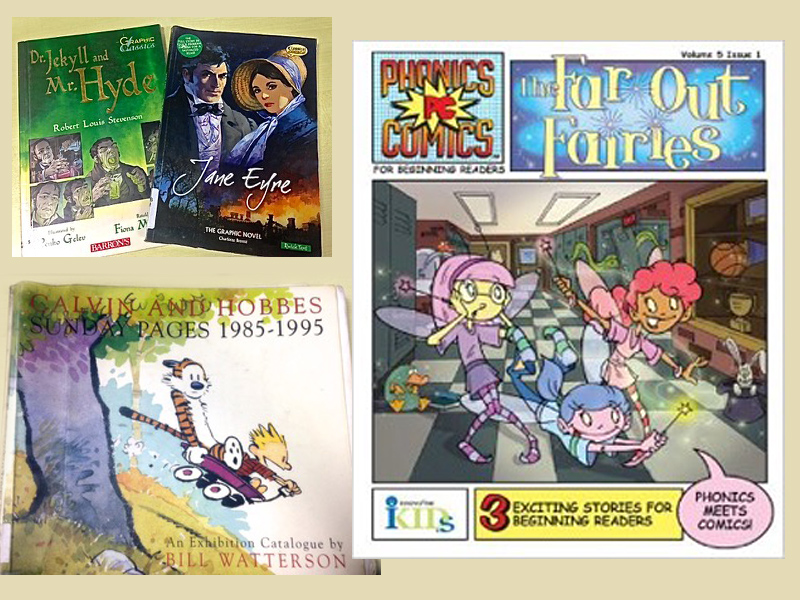

There’s a whole series of adapted classic literature, mostly American or English: Jane Eyre, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Stevenson’s Kidnapped and stories about Sinbad the Sailor.

Here, too, we have Tintin’s adventures, and a graphic novel about the “Korean Robin Hood”—The Legend of Hong Kil Dong. There are, of course, all kinds of simple, funny children’s books, such as the series “Phonics Comics” or Captain Underpants. Children absolutely love him—that’s apparent from the state of the books on the shelves here.

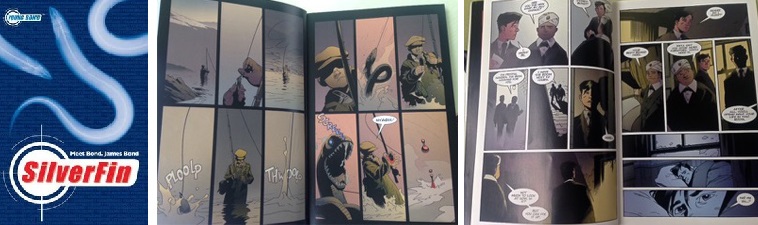

Among the endless “serial” graphic novels for children, you can find some truly interesting things like SilverFin by Charlie Higson and Kev Walker. The book is incredibly beautiful, with an unusual color palette, and tells the story of the young James Bond (fourteen years old in the story). This novel, in spite of its hefty size (400 pages) and rather complicated plot, is drawn in the traditions of the superhero comic. So what is the difference between comics and graphic novels?

Comics vs. Graphic Novels: A History

Specialists often distinguish between comics and graphic novels according to the following criteria: comics come out regularly in newspapers or journals, say weekly or monthly. They usually represent short stories. Historically, they were funny. The first American comics were comic strips in the paper, also known as the funny pages, or the “funnies,” which came out at the turn of the 20th century.

In the 1920s and 30s, comics in America came to be sold as magazines that came out regularly. Several pictures would appear on one page, accompanied by text, and were meant to be read in a particular order. This period is generally referred to as the “golden age of comics.” What we typically consider comics harks back to this particular time in American history. As an aside, the father of European comics is considered to be Rodolphe Töpffer, whose first comic was published in a newspaper in 1833. Later, in 1842, it was translated to English and published in an American newspaper.

Graphic novels are, in a sense, “grown up” comics. Unlike comics, graphic novels often feature a more intricate plot. They tend to be much longer, with more complicated heroes and themes. Though that’s not always the case, as you can see from the books mentioned earlier. The average graphic novel for children is approximately 150 pages in length, but one could argue about whether it has serious themes and heroes.

The graphic novel makes more sense as a genre intended for adolescents and adults. That audience allows for a more complex plot and the development of serious themes. But when it comes to children between the ages of five and eight, the boundaries begin to blur, and novels, comics, and picture books all start to look alike. Besides, if you were to take several utterly basic comics on one subject and put them out as one book, that too would be a graphic novel.

Even specialists often struggle to define what’s what, and that’s why such books are often grouped together at libraries and bookstores.

The issue with defining the term also has to do with the fact that, for a long time, in English-speaking culture, comics weren’t considered “serious literature,” unlike their counterparts in France or Japan. Even now, graphic novels aren’t accepted by all parents or teachers. Yet the term “graphic novel” sounds a whole lot more sophisticated than “comics” and lends the genre an element of importance. This way a child is reading a real book, a “novel,” rather than a flimsy periodical.

When it comes to what’s available for 5-8 year olds, we could call these books “graphic stories” or “novellas.” It’s important to note that graphic stories are meant to be read by a child independently. That’s why the vocabulary tends to be simpler, the words and expressions are often repeated, and the plot is easy to follow. All this matters, especially for English-language schools where there is no set reading list and the students must find material they can read and understand on their own. The key word here is “understand,” since many children start to read early, but what they get out of their reading is a different matter.

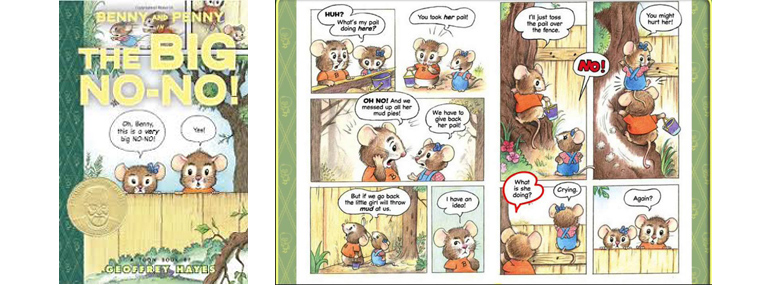

Benny and Penny in the Big No-No by Geoffrey Hayes is essentially a comic, but in a more complex format. It touches on some pressing concerns—at least, what constitutes pressing concerns for five- to six-year-olds. What should you do, for example, if your sister is a crybaby or you lost your bucket and you want to play with the neighbor but don’t know how to make friends with him? The Big No-No won the 2010 Theodor Seuss Geisel Award for the best book for beginning readers.

The text in such graphic stories usually takes the form of a dialogue between characters, and the illustrations take care of the rest. The pictures alone tell us that Penny and Benny are mice that live in a house, rather than an apartment, and that it’s summer in the story. Whether they’re crawling through a fence or hiding—there are no descriptions for these actions, just the reactions of the characters, which come through in their dialogue.

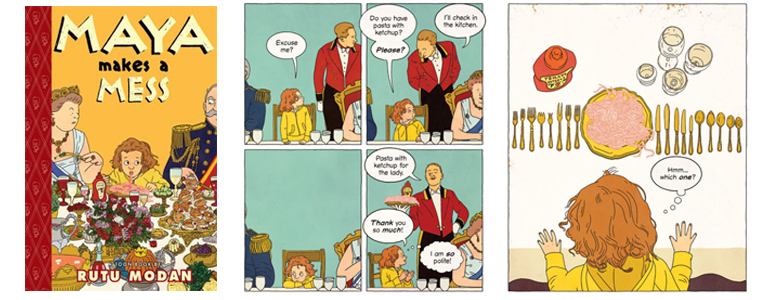

Rutu Modan’s book about little Maya, who prefers to eat with her hands (Maya Makes a Mess), includes instructions for parents and teachers about how to read graphic novels with children. What I found particularly interesting is that you should pay attention to the order and form of the illustrations themselves. For example, it matters whether there are many pictures on a page or just one. Does the picture have words or not? A large number of small pictures on one page signifies the fast pace of events, whereas a single illustration invites the reader to pause and reflect. One such example is a picture where Maya is deciding which fork to use. The more advanced the text and plot, the more obvious the difference in picture size, and the greater its importance. The same is true of the expressive color palette. In the graphic novel about the young James Bond, for example, most of the illustrations are in the noir style, to emphasize the mysterious nature of events.

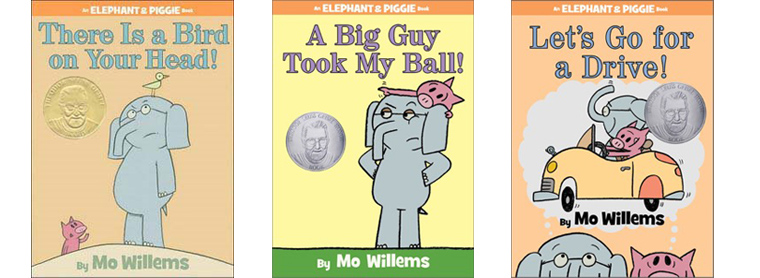

My son loves Mo Willems’s series about Piggie and Elephant. I still struggle to define what exactly they are but they are, of course, not graphic novels. They’re not quite picture books either, though, since the only text is dialogue between the characters. The dialogue is presented in the speech bubbles typical for comics. There’s no description of the characters or the setting. Judging by the illustrations and partly by the dialogues, Elephant and Piggie have very different personalities. They’re very different in general: Gerald the elephant is big and gray, he wears glasses and is calm, pensive, and cautious. The little pig is small, bright pink, has a large funny snout, and is very lively. He rushes about, full of exciting ideas.

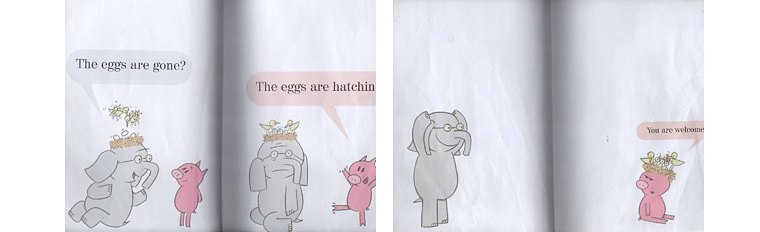

In There Is a Bird on Your Head, only the illustration conveys how perplexed the elephant is when he realizes birds have settled on his head (along with a nest, eggs, and then baby birds). Piggie helps Gerald get rid of the nest, but then it migrates to his own head. That, too, is only clear from the illustration, while the text reads as follows: the elephant says “Thank you!” to the pig for getting the birds to move off of his head, and the pig says simply, “You’re welcome!” But the expression on his face perfectly conveys the tone of his response.

The books about Piggie and Gerald the elephant are first and foremost about friendship—about how friends always help and support each other no matter what. That’s why my seven-year-old son likes them so much. There’s the story of how someone takes Piggie’s ball—some very large animal, much bigger than an elephant. Elephant helps him get it back but he feels bad for the huge lonely whale and they all play together. Then there’s the story of how Elephant and Piggie decide to go somewhere by car. The prudent elephant worries about what will happen if it rains. And what if it gets hot? What if they want to eat? Or drink? The Piggie dutifully packs for the drive, but in the end they realize neither has a car. No matter what, the characters never argue, always take care of each other, and do everything together.

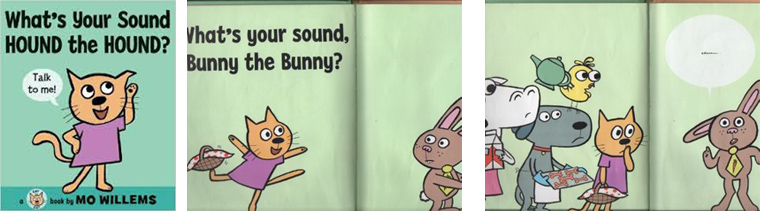

Other books by Mo Willems are written in a similar vein—Cat the Cat, for example. When she learns that cows moo, dogs bark, and birds chirp, Cat asks Bunny what sound he makes. What follows are two spreads without any words at all—the Bunny is thinking. The reader unwittingly becomes a “Thinking Bunny” too. What is he thinking about? What does that face mean? And how is he going to answer—we know that bunnies don’t have their own sound!

In this way, a child learns to understand what is outside the text, what is assumed. He learns to understand that the text only suggests, and that completing the idea and figuring out what was not said directly is an important skill, one that is usually developed more in higher grades. This skill forms the foundation for critical thinking—not just reading the words but understanding the motivation behind the words and actions of the characters, as though you were looking deeper, just behind the text (assuming there is a “deeper” in a particular book). What’s clear is that graphic novels for children develop critical thinking because children must think through to what is unsaid by relying on the pictures. The pictures are the text here. What’s more, without the illustrations, such a story either loses a significant component, or loses its meaning altogether. The picture’s unique narrative role in relating the story is key to graphic novels and stories and by no means makes graphic stories any less deserving of attention.

It’s important to reiterate that graphic novels for children are intended for independent reading. Their goal is to teach a child to read fluently and, like many books by Dr. Seuss, they are based on the repetition of words and actions. These books are accessible to kids—they’re funny, interesting, and easy to understand. How proudly a child says, “I read a book!” My son loves to check how many pages a book has—a whole 57, so many! He gets a great sense of satisfaction from reading several such books.

Maria Boston

Translated from the Russian by Alisa Cherkasova

This article was originally published in 2013

Follow us on Facebook.