The great tradition of reading before bed didn’t take root in our family. Lada is a sensitive child, not one to fall asleep easily when people are talking, when the light is on, or when there are other stimuli present. Books are among such stimuli: the story and illustrations grab her attention and don’t allow her to relax and fall asleep. Moreover, my daughter herself asks that we read to her. Apparently, she intuitively finds this activity to be “calming,” but she has yet to fall asleep because of it. That’s why we came up with a tradition of retelling books before bed. It’s dark and quiet in the room and comfy in her little bed. Nothing distracts Lada or competes for her attention. She listens to her favorite stories and falls asleep.

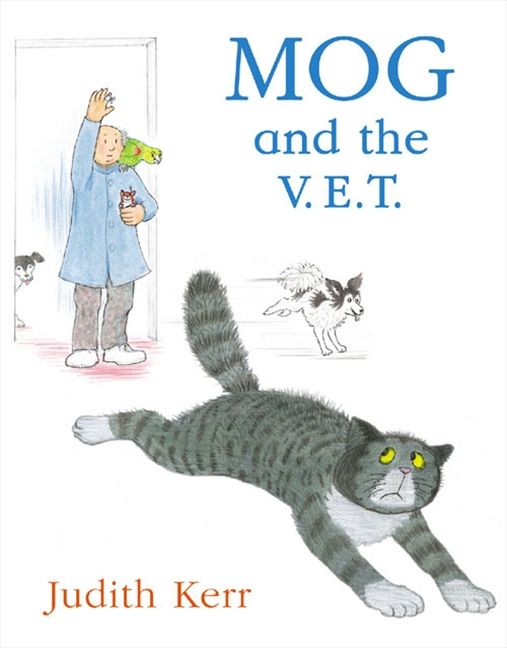

Favorite stories usually stick for a couple of weeks. Currently, they are Judith Kerr’s Mog and the V.E.T., Nick Butterworth’s After the Storm and One Snowy Night, and Axel Scheffler’s Pip and Posy: The Bedtime Frog.

Retelling a children’s book is very different from reading it. You can know it by heart, but that won’t help you much in retelling it, because half of the book is its illustrations. I understood their value only when I first attempted to retell a book to Lada. Suddenly, I found myself mumbling, stumbling and scrambling for words, and that was just a “simple” children’s story.

The thing is, illustrations not only adorn or animate the text, but also elaborate on it. When we read to a child, we keep turning to the pictures—we show them to the child, explain the text through them, and point out interesting details. We do this in passing, and often don’t notice that the child gets as much information from what Mama says and from illustrations, as from the text.

Illustration: harpercollins.com.au

For example, there’s a challenging passage in Mog and the V.E.T. Most recent English edition: HarperCollins, 2009. ISBN 0007293747.

Mog suddenly thought she liked the shut-in basket after all. The vet tried to look at her but it was very difficult.

“Perhaps this way will be easier,” – said the vet.

“There,” said the vet at last. “Now let’s have a look at that paw.”

He did something very quickly. Then he said, “All done. She had a nasty thorn in her paw, and look – here it is!”

There’s a picture for the vet’s every line. You can simply show it to a child, and the image of what’s going on will form by itself. As adults, we easily fill these gaps in our imaginations, even when we encounter the text for the first time.

But how do you tell the pictures to a two-year-old? How do you connect Mog’s unwillingness to get out with the vet’s decision to shake her out of the basket, and this decision—with the request to show the paw?

You have to come up with something, to look for words that will smoothly connect parts of the text that otherwise will be left hanging. Sure, it’s doesn’t always come out well. But I think that this activity is good for both of us. We learn to speak smoothly and coherently, to be flexible with how we use language and how we treat the imagery. We experiment, we modify the text and search for the desired form. Favorite stories become truly ours, a shared journey.

Most importantly, my daughter sleeps tight.

Irina Ryabkova

Translated from the Russian by Elizaveta Prudovskaya

Follow us on Facebook.