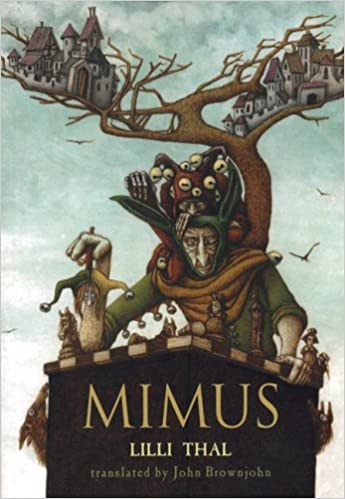

At school, we were set to put on a play based on medieval legends. You know—dashing princes and princesses, a stupid old king, an evil queen stepmother, a noble young king…and, of course, the king’s faithful court jester, a joking buffoon. Oh, how I wanted the part! Then, on the day of the read-through, my mom gave me a thick new book, with a jester wearing a cap with bells on its cover. It was Mimus, a novel by German writer and medieval historian Lilli Thal [most recent English edition: Annick Press, 2005. Translated by J. Maxwell Brownjohn. ISBN 9781550379259]. It’s the story of a king and his young prince, a boy whose fate takes a terrifying turn. The king of the neighboring country tricks father and son, imprisoning them and forcing the prince to serve as the court’s jester, a mime. Who says that can’t happen?

At first I was so engrossed, I couldn’t tear myself away. But then I started to feel that the story was dragging on, and felt it could have ended much sooner. Though that would have made it a different book, of course. I also wished it had been illustrated in the spirit of medieval miniatures. I understand that Mimus isn’t a work of historical fiction about actual historical events. It’s more of a historical fantasy. But since there are many true medieval references (like the famous puzzles written by Alcuin, a monk who tutored Charlemagne’s children), it would have made sense for the book to have a medieval design, especially for teenagers who aren’t too knowledgeable about the Middle Ages.

The text reveals the lives and psychology of court jesters. Before this book, I’d never read a serious novel on the topic. There’s Shakespeare, of course, with fools central to many of his plays, but those are books for adults. And Shakespearean fools aren’t exactly protagonists, more like personifications of wisdom and the bravery of speaking truth to power. In Thal’s book, jesters take center stage. There’s old Mimus, who’s been a slave to his profession since he was twelve, and “little Mimus,” the former Prince Florin.

Along with the prince, I traversed the stages of denial of his unusual, absurd captivity, and his growing up and coming into his own in freedom. Because he does eventually throw off the fool’s donkey ears. And what strength, mature wisdom, and bravery that takes! Where will he get it, when all he has is God and Mimus? Mimus doesn’t spare him, training him like a little dog to show off before the king who abducted him. Theodo barely feeds them, keeps them in the Monkey Tower, and doesn’t let them out except to the feast hall in the evenings. Any disobedience or excessive curiosity and they’ll be whipped by Master Antonio. The castle gates are open, but flight is impossible—because they’ll kill little Mimus’s imprisoned father. Unbearable, right?

So why doesn’t he break? Why doesn’t he become the trained puppy King Theodo wants him to be? Because he has Mimus by his side, and the older mime turns out not to be as simple as I’d thought at the start of the book.

Another discovery awaited. This book isn’t just about the psychology of jesters or princes. It’s the story of how evil begets only evil. The prince’s suffering is the result of a cruel injustice, which his father, now imprisoned, once inflicted on King Theodo’s brother. So who, we might ask, is to blame: Theodo or Philip? Both have blood on their hands. You can’t help but think–yes, a person might be free in word and deed. But they often pass the responsibility for their choices onto others, who then suffer. Like a small boy who suffers for the decisions of adult men.

It’s a tough book, but I think we absolutely need books like this one, because as teenagers we always crave freedom. And it’s worth considering its price.

Anna Semerikova, 14

Tanslated from the Russian by Alisa Cherkasova

Article and book covers: amazon.com

Follow us on Facebook.