Lately, I’m a little wary of the romantic style in literature. Romanticism sets us up for an exalted mood. As a result, we’re less interested in the “darkness of low truths.” In fact, we become squeamish about the truth, which you could call a defining characteristic of our time.

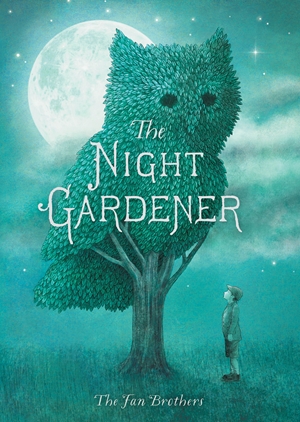

But even I couldn’t resist the romantic story written and illustrated by the Fan brothers—it was just too beautiful. Besides, I get the sense that the Fan brothers found inspiration for The Night Gardener [most recent English edition: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books, 2018. ISBN 9781786030412] with entirely realistic impressions in mind.

The story is dedicated to a sort of miracle. Still, even a miracle has an origin story. In this case the authors relegated it to a space outside the “borders” of their narrative.

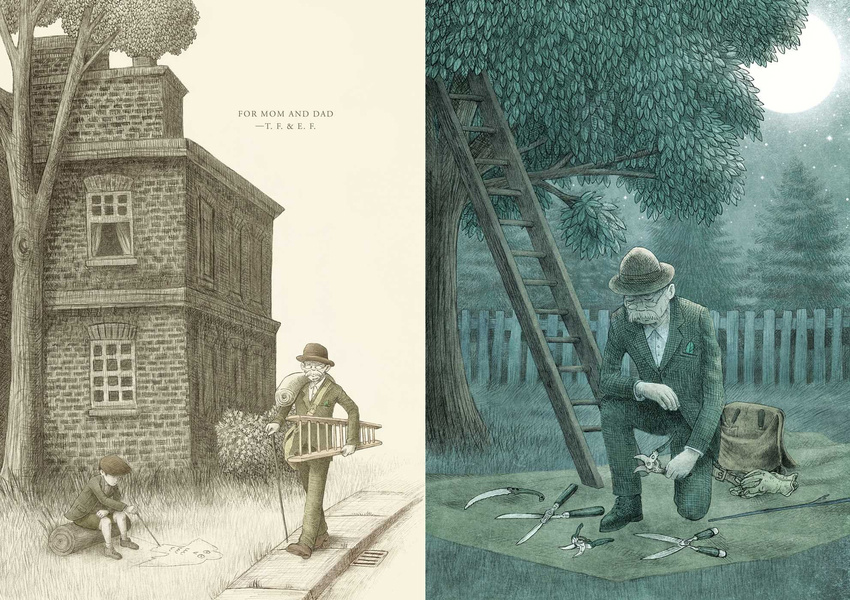

The backstory starts with a panoramic black-and-white spread that “feels” overwhelmingly gray: a smattering of people wander along a gray street lined with low gray houses. At first glance, it looks like a fairly nice neighborhood, if it weren’t for that dull grayness. The people in the street move aimlessly, hunched over, shoulders down. They’re literally weighed down with life’s worries, in the form of bags and carts. Most we see only from the back. If it weren’t for the effort propelling them forward, they would blend in with the houses, fences, and posts: their clothes are the same color as everything around them.

On the second spread—which also precedes the title page—are two different pictures. The one on the left is black and white, like the one we just saw. This time, though, there’s a lot of white in the background. The white wrangles with a dreary gray house, as though trying to push it aside. Before the house, a little boy in a jacket sits on a log, using a twig to draw a huge bird with big eyes in the dirt. Someone approaches the boy—someone we’ve already seen on the previous spread. This man had stood out from the others in the street. Even from behind, we could see his back was straight. He was the only one walking in the street, breaking with the heavy flow of the other pedestrians. Under his arm, he had a ladder, on his shoulder—a rolled-up rug, hanging by his side—a large bag. And now he’s coming “toward” us, the white background glowing behind him—a visitor from another world. He’s wearing glasses and has a thick mustache. Who is he?

Image: thefanbrothers.com

The picture on the right is suddenly, unexpectedly, in color. The color is a muted one, emerald-gray. Still, it’s color, and the light of the full white moon lends the scene an air of mystery. The man with the hat and the mustache is in the middle of the picture. His ladder is now leaning against the tree and on the rug before him he has garden shears and a hand saw. His eyes are closed in concentration. He’s trying to see something within himself. There are no words in these illustrations.

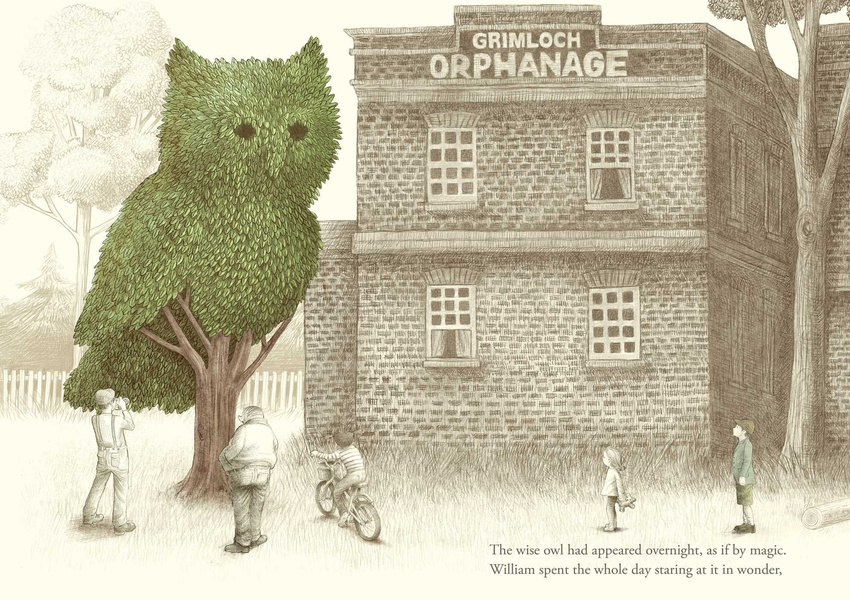

Finally, on the third spread, is the title page, with that emerald-gray nighttime feel. The title and authors’ names are written on this background in the white of moonlight. Most of the spread is occupied by a two-story brick building: “Grimloch Orphanage.” On the left side of the picture is the night gardener, up on his ladder, trimming the thick foliage of the tree right in front of the orphanage. Just three spreads, four pictures, the story hasn’t started yet, but the narrative has already reached a point of dramatic tension.

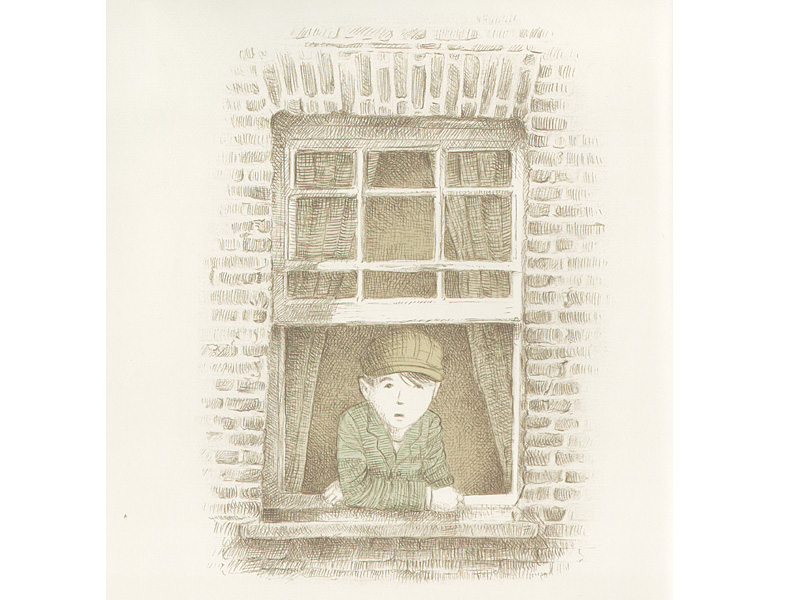

The next spread is dominated by a white background, and the narrative finally has its protagonist. The text begins. “William awoke to commotion on the street.” As William looks out the window, we’re seeing him from the outside, recognizing the boy who’d been drawing the bird. (An attentive reader will note that William’s little gray jacket has acquired a bit of a green hue.) We’ll learn what he saw and what made him run outside on the next spread: the crown of the big tree in front of the orphanage has taken on the form of a huge bird, a wise owl. The tree becomes a spot of color in the gray world that surrounds William. We understand now why he stood and stared in wonder. We realize that it’s this lovely glow that colors the boy’s jacket as he gazes out the window at the bird-tree.

Image: thefanbrothers.com

Night falls. The world goes back to gray. William is back inside the orphanage, but he won’t step away from the window. He won’t go to bed. On the windowsill is a small photograph of a man and a woman. Are they William’s mom and dad? A child might miss this detail in the book—what matters more is William’s amazement at the bird. William has come across a miracle.

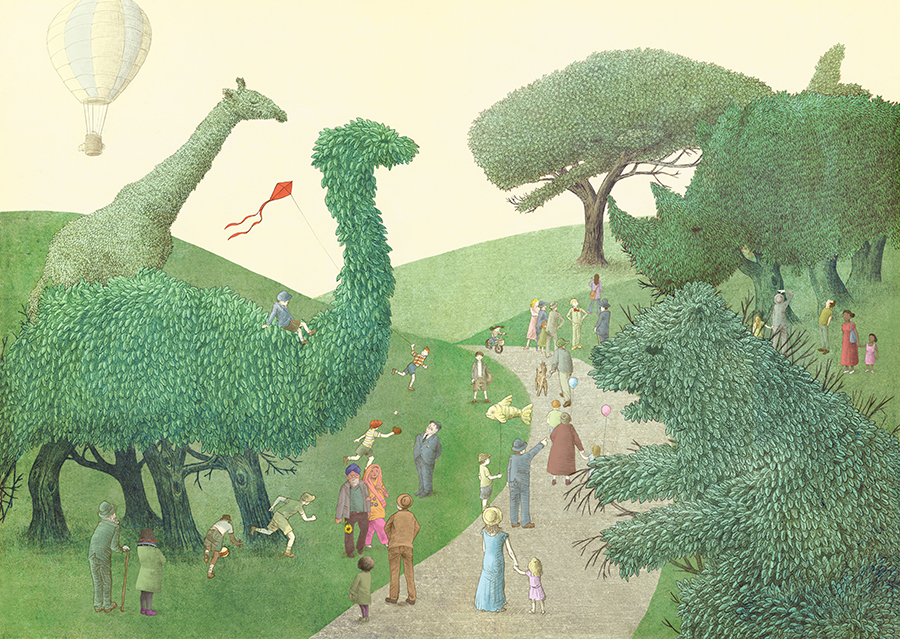

The miracles continue. Every night a tree somewhere in the town takes on the form of a living creature—cat, elephant, dragon. It’s so beautiful and unusual that the townspeople start to gather around the transformed trees. They have no particular aim but to admire and enjoy them together. We know from the backstory that each of them used to look down at their feet, preoccupied only by the weight of their own bags. The changed trees, on the other hand, force people to look up in wonder. They elicit smiles. Wonder and surprise become a shared experience. “With each new sculpture the crowds grew and grew.” The people sensed that “something good” was happening, and we, as readers, see the “living trees” bringing color onto the pages and into their lives.

It’s clear that someone is responsible for the nightly miracles. But whose work is it? Unlike the reader, neither William, nor the other residents of the town, know the answer.

The authors make us readers hope ardently for the boy to learn the secret, which he was first to discover. But just when the tension reaches its peak and the secret should finally be revealed, the night gardener turns to William and says….

What does he say? “Let’s work wonders together, my young friend”? Or “let’s bring light to the people”?

No. He says, “There are so many trees in this park. I could use a little help.”

As a reader, I’m infinitely grateful to the authors for these words, so lovely in their prosaic simplicity that I want to repeat them over and over: There are so many trees in this park. I could use a little help.

The story is a near-perfect example of the “magical story” genre: a young orphaned boy meets a wizard, capable of turning the ordinary into the extraordinary. Their encounter occurs at night, the wizard takes the boy in as his apprentice, and gives him an object with magical powers.

But what magic is there in a pair of pruning shears? It has all the magic of any instrument used by an artist or sculptor. A trimmer can transform materials, lending them new forms. It’s reality, not magic. Trimming trees is an entirely realistic thing to do—even if it’s an artistic trim. Nothing is impossible.

Romantic realism is the most wonderful thing about this book.

Image: thefanbrothers.com

There’s no ecstatic happy end proclaiming that all is now well. Instead, autumn comes and then winter, the leaves fall from the trees “until there was no evidence that the Night Gardener had ever been to Grimloch Lane.” Art has given way to nature and the natural course of things.

We do learn that the townspeople “were never the same.” What they experienced left an artistic trace inside them. The next-to-last spread is full of color. There’s this huge warm late-afternoon sky over a cozy, green little town, with the townspeople gladly spending time out of doors. You can almost feel how clean the air is, how much air there is to breathe.

Still, there’s no excess of color, it’s all subdued, with lots and lots of green. Green as the color of peace? Peacefulness?

Many of us would like to live in a world like that, and that desire makes us want to stick around in the book’s pages.

On the last page, we see William again—in the green quiet of the night, shears in hand. He trims a bush, turning it into a fox. William changes too: a new life has begun, one in which he clearly sees his place.

But all that’s for the adults. Kids will understand that William has also learned to change the ordinary into the extraordinary. He’s the talented apprentice of a magician, an artist.

You can’t deny romanticism it’s psychotherapeutic quality.

Marina Aromshtam

Translated from the Russian by Alisa Cherkasova

Book cover image: quartoknows.com

Follow us on Facebook.