“How do you get a child to like reading? How do you get him to read?” I get these questions at talks I do and radio programs I’m invited on. I get them in letters and in person. You’d think if a person writes about children’s books and spends as much time and energy on children’s reading as I do, she should have the answers, recipes for what you should do and how. That’s exactly how one radio show host put it to me: people need practical advice.

A famous writer once shared the story of how she got her teenage son to love reading. She’d wave a good book in front of his nose, then put it up on the highest shelf in the bookcase and strictly forbid him to touch it: “It’s too early for you to read that!” You could easily see the “forbidden book” on the shelf, but to reach it you’d have to get up on a chair or a ladder—make an effort, in other words, and do so while the parents weren’t around. A few days later, the book turned up under the boy’s pillow.

The anecdote elicited mixed feelings—“what a great story!,” but also “you really can’t do it that way…” Of course, I found the whole thing entirely believable. At the same time, I had the sense that the trick wouldn’t work more than once. The way I saw it, it would be wrong to draw a “methodical principle” from the incident. So teenagers like everything that’s “off limits”? Let them think we don’t want them to read good books, right? Oh, how they’ll want to read!

Teenagers aren’t fools. They can sense that we’re trying to trick them. What could be worse than feeling like you’re being taken for a ride?

Let’s just say this example wasn’t particularly inspiring. To the contrary, it reminded me, once again, that there’s no universal formula to encourage reading.

You could probably name optimal conditions: reading to your child from an early age, having books at home, constantly expanding the home library, being a reader yourself, attending plays together (this develops speaking skills), writing your child letters, writing letters with your child (reinforcing written text as an important aspect of communication)...But optimal and necessary is far from sufficient. Sadly, even all of the above doesn’t guarantee success.

Reading is an incredibly individualized activity, a form of complex communication. A child may be entirely uninterested in reading at certain points in her life, then suddenly find herself in an environment where reading is valued and has a social function—and then start to read. Or, conversely, a child may have unfulfilled social needs (not know children with a similar mental outlook and intellectual capacity) and so compensate for a lack of live interaction with peers by reading. “Binge reading” is a frequent result of teenagers’ need for intense connection. A child starts reading everything indiscriminately. We marvel: what a bookworm! A discerning adult would be hard pressed to call some (or many) of the books the young reader “devours” actual literature: It’s practically pulp fiction! How can he read that?

The child (a smart, perceptive child), on the other hand, is simply using the moment to address other issues. The challenges he’s facing aren’t aesthetic ones. He’s turning to books to find “traces of himself,” his feelings (no matter how crude or saccharine their depiction). He’s looking for guidance, recommendations (just like his parents are!). A teenager, if you will, is like any other person, and at times craves things that are unrefined or tacky. What is tackiness after all? It’s a simplified, common, “standardized” description of lived feeling. And what are you to do if there hasn’t been anything finer or deeper written about those emotions? At least, not for a child your age. You so need, so want, that lived experience (or the premonition of experience) to be called out and named.

Reading, like other forms of communication, can have a very wide range of motives. Just like we prefer the company of different people in different situations, so, too, do we prefer one sort of reading material in one case, and an entirely different one on another occasion.

A child is no different from us in this regard.

She reads to step back from reality—or to learn about it.

She reads to experience strong emotions—or find peace of mind.

She reads because she seeks new information in the form of dry facts—or she might find that facts mean nothing to her without an emotional delivery.

She might be looking for a clear, simple logic—or hoping to be entranced by the mysterious and mystifying.

A child reads to feel smart, kind, powerful, to find a reason for being or to be forgiven.

She reads with different intensity and different expectations for content at different ages.

Reading can get “professionalized” with time. Or it may become exclusively a leisure activity.

I say all this to back a simple thesis: each child has their own way as a reader. You have to develop an individual “roadmap.”

I’d go as far as to say that reading skills are a certain gift. Some children have musical gifts from a young age, some have an incredible sense of rhythm and ability to perform difficult choreography, others spend hours building spectacular constructions from anything at hand. Some construct complex plots for games. Others get on a bike and zoom off—they have no problem with balance and coordination.

And others, with no adult involvement, discover reading for themselves as a form of communication and truly enjoy it from the very first pages.

Yes, there are child geniuses of sorts who are naturally gifted at reading from an early age.

And then there are the kids that need time to start reading with pleasure. They’re often the ones that need our patient efforts the most.

But as I’ve said, there are no universal formulas. There’s no magic key that opens all doors out there. Each door has its own key.

It’s not the prescription that matters here. What matters is a diversity of experience: different ideas, unexpected successes, lucky coincidences we can share with each other. They’re not a panacea—it’s nearly impossible to reproduce another’s experience. But we can find inspiration—use an idea to push off of or mold it to our needs and the capacities of a given child (and those of a given adult).

***

I once heard about a sweet eight-year-old girl who was very mature for her age, a straight-A student, loved by kids and adults alike. But she didn’t care for books at all. The parents, of course, wanted their otherwise perfect, lovely daughter to read, too. After, all, they’d read so much when they were kids!

It’s clear there’s a key factor left out of the equation: if the girl’s parents read a lot as children, that doesn’t mean they still do. Otherwise they wouldn’t emphasize how much they’d read before. These days, of course, they’re very busy with work. They don’t have a lot of time to read aloud to their daughter. But they love her and want to make her happy.

I suggested to the parents that they turn book gifting into a game. Buy lots of picture books—beautiful ones you can’t tear your eyes from, ones that beg to be opened. Ideally, they would be slightly below the girl’s reading level—in other words, easier than texts required for school reading.

They could wrap the stack of books, so you can’t get at it all right away. And let’s say the book parcel gets delivered by an unexpected guest, someone who comes in and says: “Is this a very smart little girl’s home? This is for her—just for her!”

I know it’s a game for people with some means. It’s also true that even if the girl enjoys the game, there’s no guarantee of a lasting result.

And there’s an obvious weakness in this plan. I couldn’t help but put myself in the girl’s place, trying to imagine how I would respond to the game. It’s probably not the right way to think of things—we live in a different time, and little girls are also different. Still, we have to start somewhere to think of something. Something specific to this situation.

Now if I were eight, and I got a curiously wrapped package and I opened it...

...and found...

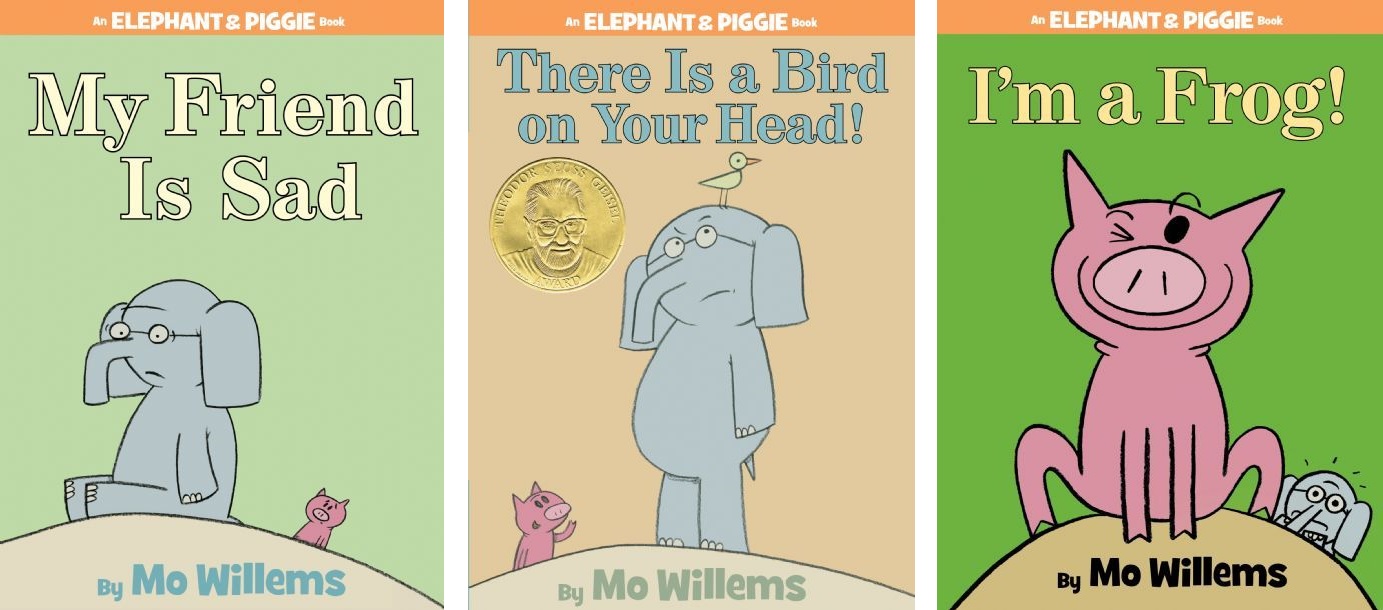

Let’s say I found several “volumes” about two best friends— Elephant and Piggie.

Book covers: scholastic.com

And let’s say those books by Mo Willems had lovely big letters (like someone lending you a hand as you go uphill!).

And there’d be just a sprinkling of words to read, here and there! What a gift for a beginning reader.

Everything is clear and easy to understand...

I’m reading! I’m actually reading! Turning pages one after another! Reading such a thick book. (All Elephant and Piggie are available in real hardcover.)

This isn’t some “Dick and Jane” reader. It’s a thrilling story with subtle, sophisticated, absurdist, humor.

I’d think: cool! Cool pictures. Cool characters these Elephant and Piggie. And what’s written on their little faces generously complements the words on the page. It’s so lucky there are five books: you can prolong the enjoyment.

So I’ve read five books? Oh my gosh! I’ve read five whole big fat books!

I’ll probably read them over again tomorrow.

It’s not at all intimidating. Or boring. It doesn’t feel like work at all.

Someone, anyone, give me more books!

Naturally, there are a lot of stretches in this imagined “reenactment.” At eight, I didn’t use words like “humor” or “absurdist.” At most, I would have said, “that’s funny!”

Besides, our society’s relationship to humor, and what it stands for, has changed significantly. In my Soviet childhood, you had to say the author was making fun of the characters’ bad personality traits, that he was criticizing them and that they should change for the better.

But Elephant and Piggie don’t have any of that negativity. Mo Willems’s plots aren’t didactic. They’re about something else entirely—how we see ourselves, how we appear to others, how we are consumed by things we want and don’t want.

A nest appears on our heads out of nowhere, a nest with birds in it. The birds decide to lay eggs. And there’s nothing you can do about it—you have to live with that nest.

Live with it, just like we live with that thorny question: how the heck do we get them to read?

Translated from the Russian by Alisa Cherkasova

Cover image: flickr.com

Follow us on Facebook.