We all know how to do “timed” reading—back at school teachers would push us to read faster with a timer, and now they do the same to our kids. But a real understanding of books and love for reading come when you read slowly—very slowly. That was the kind of reading that had entranced my young children and likely how they learned to truly enjoy reading. As they grow, however, children often want to devour books with an expliting plot. They skim the surface, reading faster and faster to learn what’s next, will he kill him or not? As for the technical, informative, “textbook” reading taught in schools—that skill often doesn’t allow children ages nine and up to really hear the melody of the text, to think through or marvel at the depths of meaning. It could well be time to go back to slow reading. Still, as kids approach their teenage years, they aren't exactly thrilled to gather for read aloud. So what to do?

The solution arrived unexpectedly. It occurred to me (I’m a historian by training) that in the olden days—in Egypt, in antiquity, in the Middle Ages—people always read slowly. They only read aloud, too, and with expression. There was a simple reason for this: there were no spaces between words. So you had to properly intone the text, looking closely at its structure. Slowing down allowed you to take in the meanings and make observations. Plus, the manuscripts were written by hand, and rewriting and rereading them cultivated attentiveness. So I thought, why not take this cultural studies approach to meaningful reading with preteens? Learn to take in the text attentively, while immersing ourselves in learning about new cultures?

I knew for sure that I wanted to avoid school walls or any formalities. We soon found a cozy space for our meetings—a children’s club on one of historic streets in the center of Moscow. It was the perfect place, always full of children, great books, and involved parents. This fall we started reading the Iliad in a small, comfortable, homey room full of bookcases.

That’s right. We decided to read the Iliad. And to read it very slowly. As soon we agreed to stop racing through the lines of text, stop leaving the flourishes (like “under the aegis of” or “richly-dight shield”) undiscussed, the text revealed itself to us. We didn’t do anything special. We put an hourglass on the table to measure out one minute. As the grains of sand poured down, each of us sitting at the big common table (myself included) read their own piece of text, pausing at all the punctuation (wasn’t that what it was for, after all?).

Here, everything was the exact opposite of what school usually demands—in a minute, you have to read less rather than more words. The only condition is you can’t break them up into syllables. As if by magic, the huge, often intimidating brick of the Iliad came to life, spoke to us. We heard the grand bronze of Greek hexameter ring out. The children physically felt the momentousness and gravity in the vibration of their vocal cords. Many straightened their shoulders as they held the sheet with the text before them. That was another thing we’d thought through—a sheet of paper rather than a heavy tome. No terror before the unfamiliar classic.

What did we read? To take one example, we read the list of ships that set off to return Helen of Troy to Sparta. We took the time to count how many there were. We learned that “Myrmidons,” the soldiers led by Achilles, means “ant-people” in Greek. Someone immediately asked: why ants—because the Myrmidons were short or because they were hard-working? This was it! When children ask questions, we’re on the right track, engaging fully with the text.

Of course, we didn’t just read. The children would have quickly gotten bored for lack of practice. At the end of each session at Manuscript Slow Reading Workshop, the kids do text-based crafts. When I watch my own kids or remember my childhood, I know how important it is to play with the text you’ve come to love, make figurines of the characters to relive their adventures—on the tips of your fingers and in your imagination. Since we’d wanted the Workshop to have a culture studies slant from the start, we make artifacts from antiquity or the Middle Ages. We read about ships and then build our own trireme. Each child takes home their own handmade Greek ship. A week later, we read about the fight between Hector and Achilles and make a copy of Achilles’s shield, still considered an important source for historians studying Ancient Greece. One boy later made a plywood version at home. We read about the fall of Troy and make a Trojan Horse on wheels. And we take the opportunity to learn that Homer never told this story—it was put together entirely from the texts of other writers in antiquity. We read a compilation of Greek myths for children and look at copies of statues and temples from Ancient Greece. In the breaks between reading passages, I retell the whole plot of the Iliad and the history of the Trojan war from the mythological and archeological standpoints. Most importantly, we address the children’s pressing questions about the Greeks. An hour and a half flies by in our workshop.

At first, the parents would bring the kids in. The kids were clearly unhappy to be there, wary even. Reading, again? Out loud, too? In front of everybody?! But their skepticism gave way to fun. Now each time we meet we have ten to twelve kids ages 8-12. We don't have an objective of bringing more children into each group—we simply announce a repeat of a series for new groups. Slow, attentive reading is a singular kind of work, an intimate process not unlike copying out ancient manuscripts by hand.

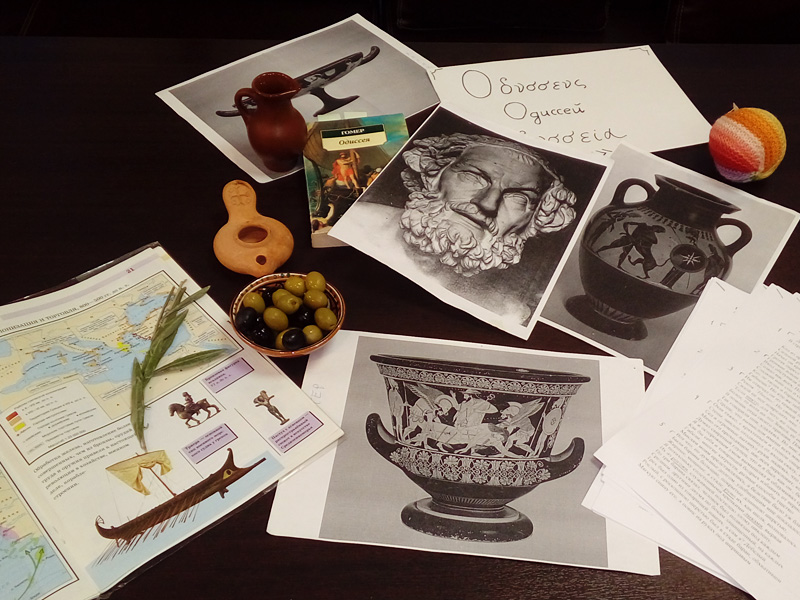

Over the course of a year, our repertoire of texts significantly expanded. The Iliad was followed by the Odyssey (also explored by reading particular passages, and a colorful retelling for the rest). In the wake of Odysseus’s travels, we made amphoras and a tactile three-dimensional map of Greece. Naturally, we made a mythological map of his travels to go along with it, deciding which Greek islands could have housed the Laestrygonian giants, the sirens, or the enchantress Circe.

For another reading series, “Songs of the Sea,” we read Viking war songs and immersed ourselves in their unusual culture, which has always exerted a strange fascination on children. Not just boys, either—the girls loved building their many-oared dragon-headed drakkars. We read the songs of Irish missionary monks of the early Middle Ages, who may have arrived on the shores of North America in leather boats nearly five hundred years before the Vikings.

In the winter, we read Christmas stories and discussed their distinctive characteristics, along with the details of everyday life in cities and villages of pre-Revolutionary Russia. We learned many strange new words, which no one would have found strange just 100 years ago. We built a shining Christmas star and a paper angel, read a modern retelling of the Biblical Christmas story and constructed our own nativity puppet theatre out of paper to act out the 2000-year old story. The children, ringing little bells over the pages of the book with just the soft glow of a pocket flashlight, felt like they were a small part of this story, too.

It’s not a club or a studio, where attendance is required, or at least regular. Each get-together is stand-alone, but since kids find themselves in a space where their interest freely develops, where they’re free to ask the questions they want about books and culture, they come again and again. And we think up new series: Old Russian historical chronicles, medieval knights’ legends. We will read very slowly and clearly and try to write out the square lettering of Old Russian manuscript tradition and the sharp Gothic script of Medieval Latin, make ourselves a coat of arms and maps of journeys and wanderings.

I think we've found the right rhythm.

Elena Litvyak

Translated from the Russian by Alisa Cherkasova

Follow us on Facebook.