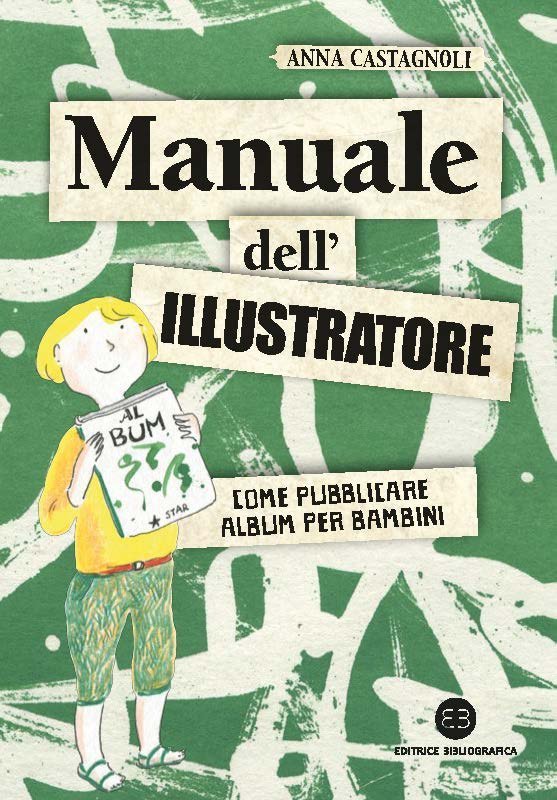

Anna Castagnoli is a children’s book author and illustrator, and lecturer. She has served as a jury member for a number of prestigious illustration competitions and has selected works for exhibition at the Bologna Book Fair. In 2017, her textbook on illustration was published in Italy [Manuale dell'illustratore sottotitolo. Come pubblicare album per bambini. Editrice Bibliografica, 2017. ISBN 9788870758863].

Image: editricebibliografica.it

For the last several years, Anna has lived in Spain, where she teaches, and collects vintage children’s books. This fall, the Bologna Children’s Book Fair was guest of honor at the Moscow International Book Fair. That’s how Anna Castagnoli ended up in Moscow, where she sat down for an interview with Papmambook Editor-in-Chief Marina Aromshtam.

- Anna, you teach future book illustrators. Obviously, they need to be good at drawing. But is there something else they need to learn? What should they understand about illustration?

- Back at university, I studied philosophy and I find it very important to understand the specific nature of each phenomenon. Illustration is a very particular genre within the visual arts and it needs to have its own language, which differs from that of easel painting, for example. So it’s interesting and important to understand what those differences are, as well as to understand the principles of illustration, the traditions behind it.

- Do you mean the principles of illustration more widely or the principles of creating a picture book? I would argue that these are two different things. One of the main principles of the Soviet tradition of illustration was: “The illustration must serve the text.” The artist can, of course, add details to a character’s image, but she cannot tell a parallel story that contradicts the author’s tone. Yet, in picture books we see that all the time. Still, graphic arts in the form of picture books were very underdeveloped under the “late” Soviet Union.

- That’s partially true. What’s interesting to observe here is how the book changed as a whole. As literature changed, illustration changed along with it. In the 19th century, writers described their characters in great detail—what they were wearing, what the setting was like. Literature like that could do without illustrations altogether. Then, a new kind of text emerged, one without detailed descriptions: picture books. In the West, Randolph Caldecott is considered the forefather of picture books. This is in the final quarter of the 19th century. He illustrated the poem “The House that Jack Built.” The book included an image of a man pointing to a house.

Image: gutenberg.org

- That is, the text never mentioned this man. He was a character created by the illustrator, a sort of discovery on his part. The text and the illustration fused in Caldecott’s book.

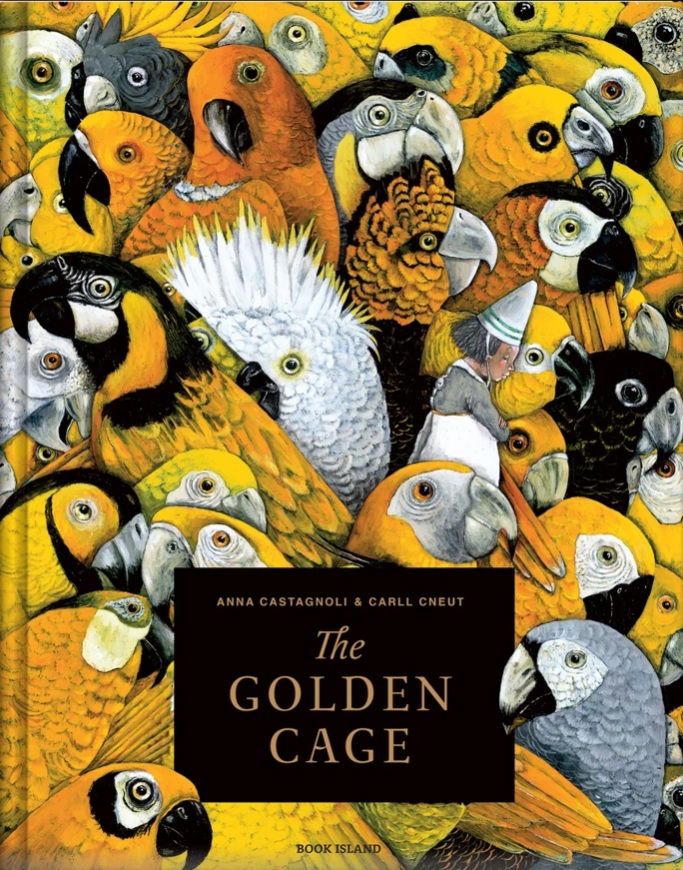

- Yes. So now there was a book where the pictures and text were inseparable. With a book like this, the author and illustrator are equally important (and earn the same amount for their work). Here, you can’t say “the illustration serves the text.” I’ll use a book I wrote, [The Golden Cage], as an example [English edition published by Book Island Limited in 2019. ISBN 9781911496144]. This story (rather macabre, I’ll admit) is about a princess who collects birds. But if she finds a bird uninteresting or useless (if it can’t pick fruits, for example), the princess has the servant who brings it beheaded. One day, she dreams of a talking bird. She announces that if someone gets her that bird and the bird speaks, she will stop the executions.

Image: bookisland.co.uk

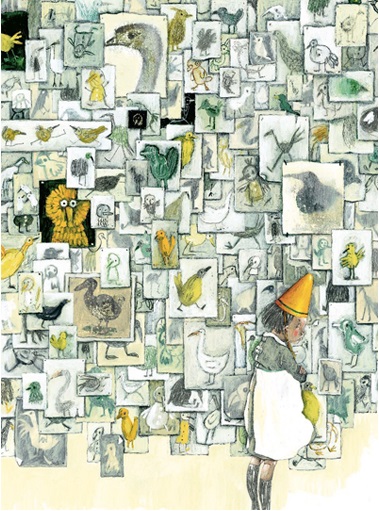

There are no descriptions in this book. But look what the illustrator, Carl Cneut, did, what he came up with. First of all, he imagined the palace and garden where the princess keeps her birds. There are birds with crystal combs and gold beaks, which the text never mentions. But we know the princess collects exotic birds! So these details are an extension of the author’s ideas.

The illustrator also decided that a girl obsessed with birds might enjoy drawing them. The princess’s room is full of drawings. When the princess dreams of a bird, she draws it. And when her dream becomes reality, the bird looks real too. When the artist illustrates the princess’s dream, his style changes again.

- It‘s stunning.

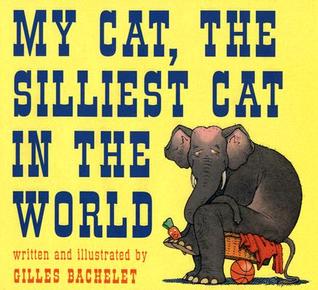

- The book has been translated into seven languages and won many awards. I don’t think it would have been as successful, if the illustrator had stuck to “serving” the text. Here’s another example: have you heard of My Cat, the Silliest Cat in the World by French writer and illustrator Gilles Bachelet [English edition published by Harry N. Abrams in 2019. ISBN 9780810949133]?

Image: goodreads.com

- Yes. In Russian, it’s been translated as My Cat’s Personal Life. But the illustrations feature an elephant, not a cat. The narrator calls his pet elephant a cat and tells us what the “cat” gets up to. Everything he does would be normal for a cat. But when an elephant does the same thing, it’s ridiculous and bizarre. That’s what makes the book funny for the reader.

- I think it’s very good for a child to compare what’s drawn with what’s said and discover contrasts between the illustrations and the text.

- It would certainly be impossible in a classic illustrated book.

- Exactly. Illustrations give the text immediacy, a “here and now” feel. Let’s say the text mentions a tree. The artist decides how to draw that tree, whether it’s going to be an apple tree or a birch. The way he draws the tree will impact the meaning.

- This may be one of the reasons illustration has so many opponents, particularly among writers. Tolkien said something to the effect that when he writes about a mountain, he doesn’t mean a specific mountain, but rather a mythical one. A mythical mountain can’t be drawn, according to mythologist and philologist J.R.R. Tolkien.

- Kafka also asked that the cover of his Metamorphosis not picture an insect. This is a tricky issue. But for eight- to nine-year-olds, the blending of the picture and text works. It’s supposed to help children learn to read. Of course, now we have books coming out that have no text at all. This is a new trend that many people are uneasy with.

- Would you say this could lead to the disappearance of literature as we know it?

- That’s hard to say. Literature, after all, has played an important role in society for a very short period of its history. I would hope it doesn’t disappear, that we continue to have wonderful new works. But I think what matters more than literature continuing to “exist,” is that we continue to tell children stories. That’s more important. The language we use to tell those stories is separate issue.

- I think we’ve come full circle. Getting back to the principles of illustration, could one say that there’s an interesting story at the heart of each picture book?

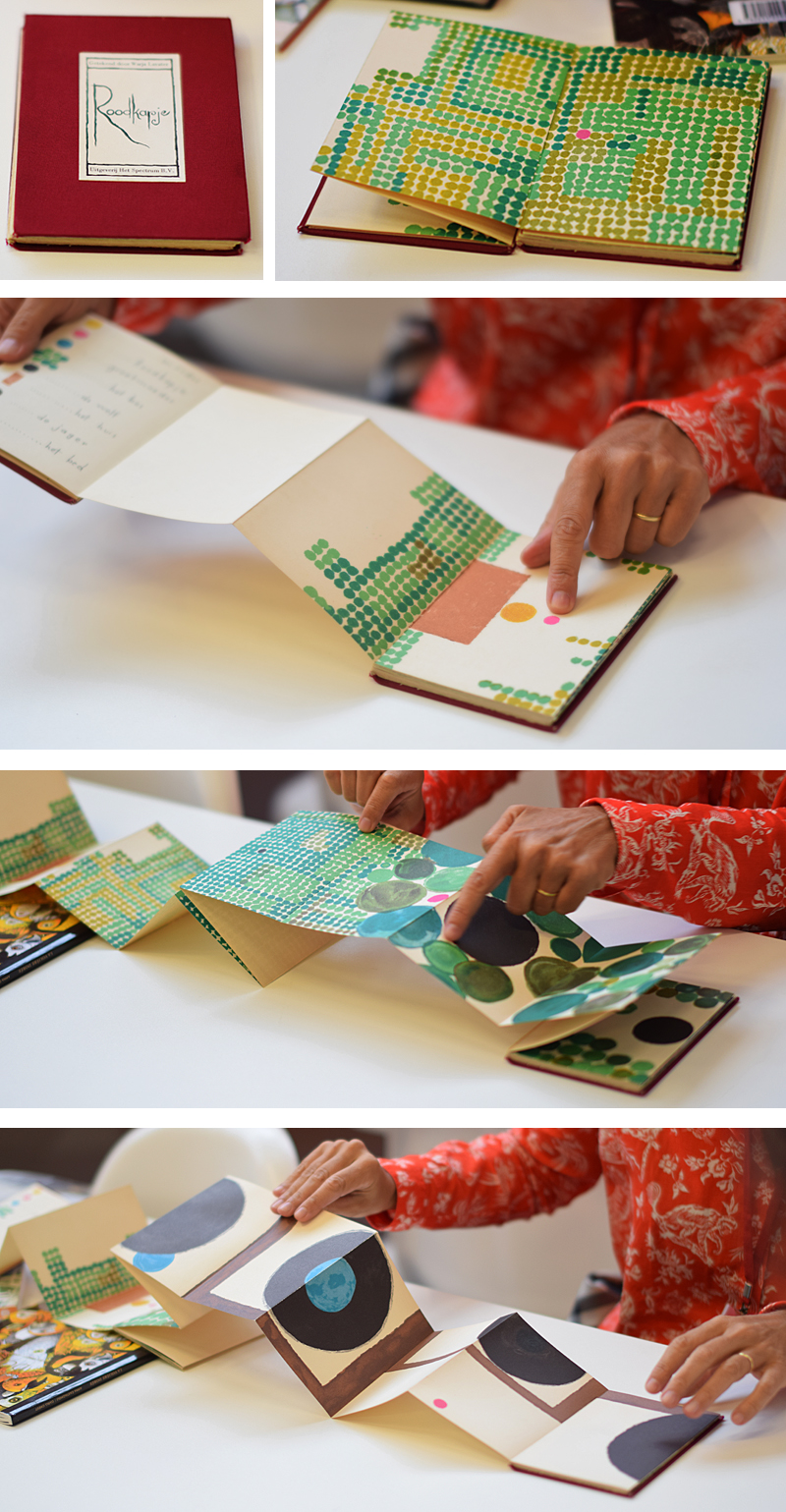

- Yes, of course. In the children’s book as we know it, there’s always a story. But it can be told in different ways. Take for example “Little Red Riding Hood,” as envisioned by a famous Swiss illustrator, Warja Honegger-Lavater (who has books on a range of other popular folktales). The characters don’t look the way we’re used to seeing them—they’re all represented by dots. Here, the storytelling emphasizes composition and color. But if you ask a child who the main character is, she will immediately point to the right dot. Even two- or three-year-olds get it. You do still have to show them, this is Little Red Riding Hood and this is the Wolf and then the child is able to follow the “motion” of the dots and enjoy the story.

- So the child still needs that adult voice accompanying the book, reading the story aloud.

- And that’s wonderful. As I see it, there should be all kinds of books, including those a child can’t fully understand without Mom’s help. This creates additional space for dialogue between parents and children.

- True, though parents aren’t always happy to have that extra space. They come home, worn out from work and hear: “Please read me a book.” And when the parent opens the book, she finds that there’s more than just reading involved. She has to put in extra effort, and it’s not always clear what she’s supposed to do. Parents don’t always have the energy for that.

- There is that issue, of course. Such pictures books are also seen as complex in the West.

- How would you describe these so-called “complex” books? What are their distinguishing features?

- It’s easier to show than tell, of course. The book about the princess, for example, sold quite well in Northern Europe. In Italy, it sold thanks to my name on the cover. In Spain, it didn’t do well at all. Potential readers found it too difficult.

- It’s usually parents or other adults that issue these verdicts. Children, as you’ve said, can “see” Little Red Riding Hood in a little dot, if an adult helps them out. What is it that differentiates Spanish parents from their Scandinavian counterparts?

- Spain is a Catholic country. Catholic traditions are still very strong there, and they dictate that children should be protected from unpleasant experiences or grim stories.

- Clearly, these views are common to all religious traditions. So, something “unpleasant” is a sign of a book’s complexity.

- Though it’s all relative, as you understand. What does “unpleasant,” mean? A child can’t grow in an artificially sheltered world. He has to learn from somewhere that there are unpleasant things in life, too.

- Right—how will he learn to relate to them, otherwise? What would be considered complex in terms of the illustrated visuals?

- I would put it this way. A simple illustration is one that is much more realistic than a complex one. In a complex picture, the image may be flat, and the background stands out. This invites the child to examine it, which is precisely what gives a complex picture its educational potential. You know, there isn’t a single study that suggests that a child understands simple pictures better than complex ones.

- Books, after all, are chosen and bought primarily by adults. But the fact of the matter is that adults gravitate to products of popular culture. That’s why publishers, too, try to steer clear of complex illustration. They say it outright: if we had known that this book would do so well in stores, we’d choose a more “popular” artist for it, without any elitist quirks, or “art house” elements.

- There’s a lot of tension, which we see in Europe as well. Adults try to buy something simpler, so that children ask less questions. Meanwhile, sales of adult books are plummeting. But adults, too, need to be educated. It’s vital.

- The complex ones demand work to understand them. Since you’re thinking, it’s harder to be manipulated.

- That’s exactly right. It’s something adults need to be taught, and picture books and exhibits can further that education. The Bologna Book Fair hosts an exhibit of illustrators. When I was on the jury, it consisted of two illustrators, the director of an art museum, and a publisher. This always leads to a clash of ideas. Artists want one thing, publishers another, and a museum director something else entirely. We were given 3200 submissions. If none of the four liked a particular work, it was excluded from the contest. But if at least one member of the jury spoke up for a given work, it stayed on for further consideration. After our first run-through, we had 300 or so submissions from the original 3200. There were twelve, I believe, that won approval from all four members of the jury.

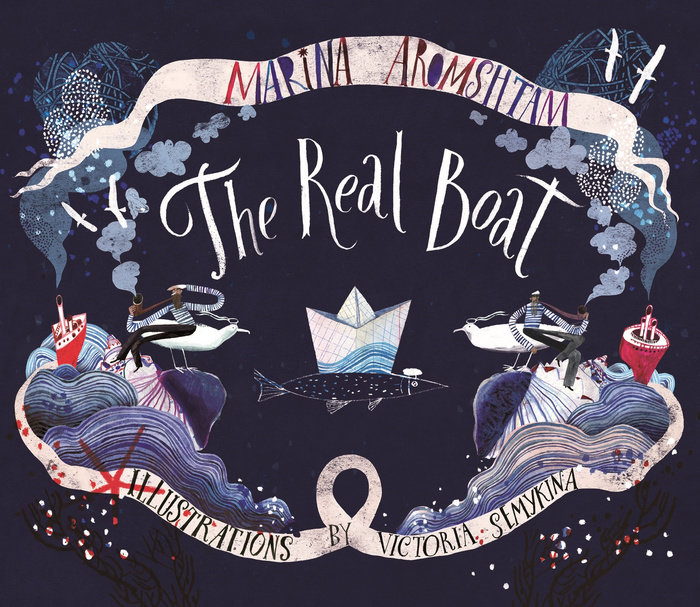

You know, many well-known illustrators started their careers in Bologna. In 2019, Anna Desnitskaya was among the illustrators on the jury. Victoria Semykina of The Real Boat also started out in Bologna [English edition: Marina Aromshtam. The Real Boat. Templar, 2019. ISBN 9781536202779]. The [artistic] “language” that is developing in Bologna is one that illustrators from around the world use in their work.

Image: penguinrandomhouse.com

- So, a museum director can come to see eye-to-eye with illustration artist Anna Castagnoli after all?

- Yes, though a museum worker is accustomed to paintings. And paintings are not illustrations.

- Is there a fundamental difference?

- Absolutely. The characters in a painting can look out at the viewer. In a book, generally speaking, they cannot. The character in a book should live through the story, travel down the book’s “path.” He can’t look right at the reader. A painting is more like the cinematographic space, while an illustration in a picture book is more like theatre. Its characters move as though on a stage, traveling from page to page. And then there are the relationships between various characters. These, too, exclude the viewer, who observes them from the side.

- So the modern illustration artist can’t think in terms of separate images. He should think in terms of the story, in terms of the whole book.

- That’s absolutely right. A common mistake beginning illustrators make is that they believe they can draw a single, stand-alone illustration for a book, even a front-facing one, as though they were going to post it on Instagram. A picture can be very beautiful, but not tell a story. Then it’s not an illustration. When the illustrator presents her proposal to the publisher, he should have the whole story in mind.

- A story is a dynamic, is that right?

- Of course.

- And that, according to Anna Castagnoli, is what future illustration artists should know.

Interview by Marina Aromshtam, with help from Italian interpreter Ksenia Yavnilovich

Photos by Vasilisa Solovyova

Translated from the Russian by Alisa Cherkasova

Follow us on Facebook.