About five years ago, at a major education conference, we were discussing a painfully familiar and ever-relevant topic: how to cultivate a love of reading in children. At the time, this wording didn’t bother me. But I decided to bring in an essential condition: it’s not just reading we wanted the kids to love, but quality reading. Children shouldn’t just read—they should read good books. Reading bad books, I thought, is not all that different from not reading at all. Maybe it’s better, in fact, that they not read at all then. At the time, others objected: let the children read something, anything. Reading anything at all is better than reading nothing, and so it’s important to support them in reading in general.

It seemed to me that reading “garbage” would discredit the process itself. Why did I want my own kids to read? Because I wanted us to have a common language, shared points of reference in the cultural space. And for that to happen, we needed to read similar books. Books, after all, are like people. The books you read are your social circle, and they set a certain cultural standard.

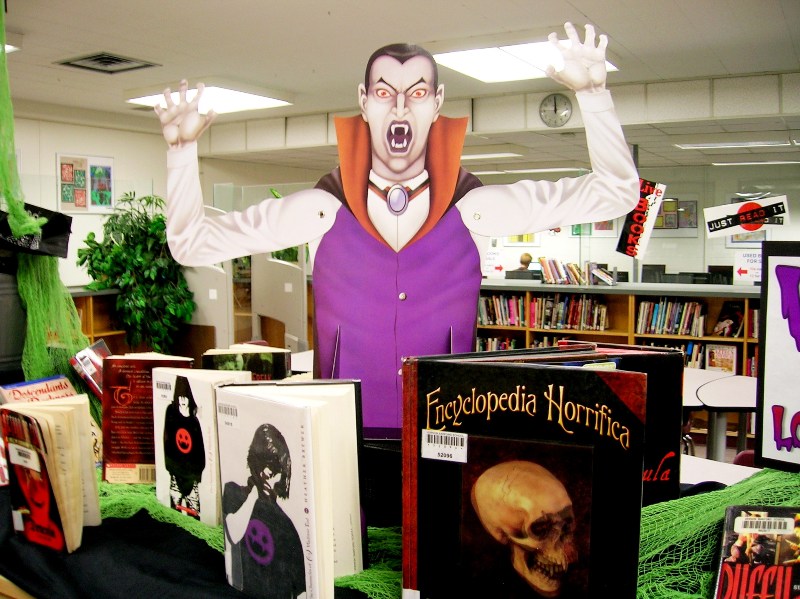

My line of thinking went as follows: I have a high standard—naturally, the books I choose for myself and my kids are good ones. What is “good,” you might ask? Good quality: written well, in terms of literary style, and complex, in terms of the experience described—in short, books that make you think. I thought these criteria were fair. According to them, plenty of mass children’s literature didn’t pass as “quality”: interactive books, sticker books, girl books, cartoon books, books about vampires or superheroes. Oh, and there was plenty else that didn’t fit the bill.

And then something unexpected happened. It was during a trip to a distant town, where I met with fifth- and sixth-graders from an orphanage at a major event hosted at a library. I could see at first glance that these children didn’t read anything, that they found reading difficult and even unpleasant. I also knew that, for these kids, “cultivating a love of reading” was not the first item on the agenda.

But I had to do something, say something “library-worthy” to these kids, anything. I took a deep breath. Hello, I can tell you a story. What would you like to hear about? There was noticeable animation in the audience and they showered me with ideas. Let’s just say they weren’t quite what I wanted to hear. Vampires! Werewolves! Tell us about the Devil! At least they knew what they wanted, what they were prepared to talk about. So it was easy to agree: sure. I’ll tell you about the Devil. And vampires and werewolves. I said those awful words and tried hard not to look at their chaperones: they had brought the kids to what they thought was a cultural event. They were promised a serious speaker, from Moscow. I felt them tense up: what was this?

What could I tell the children about the Devil? I didn’t have to think long. I had just finished writing a new book and I understood—that material would come in handy here. I started off about the Pied Piper. According to one interpretation, it was the Devil himself in disguise…. Then I told them about how vampirism may not be an entirely fictional phenomenon. Don’t assume it’s all horror, either, or necessarily about human victims. Some people lack certain nutritional elements, due to dire living conditions. In those cases, drinking blood is normal. Not human blood, of course, but animal blood. For example, the hunters of the Far North were forced to drink the blood of the animals they killed, or they wouldn’t have survived the harsh conditions of the Arctic winter. It’s so cold there that your eyelashes break if you just touch them. And then there’s the polar night. As for werewolves...let me tell you about the Siberian shamans.

I managed as best I could, using all the resources I had at my disposal. The chaperones relaxed—not completely, of course, but the initial tension in their faces dissipated. After the event, they said to me: you did it! Did what? Managed to hold the kids’ attention. We’d all wondered if it would work. We know how to talk with them, but sometimes people from the outside...

But all that was beside the point. The point was that one boy, Sergei, was absolutely captivated by this talk of shamans and Pied Pipers. He didn’t want to leave at all. He wanted to hear more. I told him: we don’t have time now, your group has already lined up to go. But I promise to send you some books.

I got back to Moscow and headed to the bookstore. I was buying books for a child that didn’t read, but who had enjoyed talking with me. He wanted a continuation of the dialogue we’d had, a dialogue on a subject that he’d found interesting. So I had to find a book to replace me. Where would I set about finding the necessary books? In the section for young intellectuals? Among editions from my favorite publishers? No. I spent two hours digging through shelves with coloring and sticker books, books about superheroes and bad guys, books about all kinds of monsters and ways to fight or tame them. For the first time in my life, I judged books not according to my usual criteria of “quality,” but from an entirely different point of view. I imagined the package arriving at the orphanage, imagined this boy opening it. How would he look at what he found inside? Would he know what to do with it? Could he get through this much text? Would he find it interesting? Would he figure out where to color and where to stick the stickers? Thanks to this boy, I discovered a new side of life, including the world of stickers and coloring books.

This wasn’t the first time I’d had to deal with the collapse of my own educational extremism (which was, of course, meant to achieve the highest educational ideals). A telling situation occurred when I was still working at a Kindergarten, back when I was fascinated by Waldorf education.

I had just come back from a lecture about Waldorf toys. The speakers had made a very convincing case what a “good, quality” toy should be like. They talked about how such a toy would affect a child, how it subtly teaches him and directs him to the right views on life. This made a huge impression on me. I decided to act quickly, decisively, and ambitiously. I called the parents in for a meeting, shared what I had just learned, and suggested we rebuild the group’s arranged environment from scratch. I gave a fiery speech and spoke persuasively, and the parents agreed.

We got together the following weekend, threw out everything that even remotely resembled play weapons, put away all the “ugly” blocks and “wrong” dolls. In short, we set about saving the class from “poor quality” toys. The moms sewed little dwarves, the dads carved trees that were straight from a fairytale. I put out beautiful little baskets, full of pinecones and cloths. It all looked magical: so soft, round, kind, all in one style. We could barely get enough of this paradise we’d built with our own hands.

In the morning, the kids came in. For the first half of the day, they walked around quiet and in awe, taking in the “scenery.” Then the novelty of it all passed and they realized that there was nothing to play with. Nothing to play familiar games with, their favorite games. Before I knew it, the boys had grabbed the trees growing in magic groves, threw them onto their shoulders, and—Abra Cadabra!—they were no longer trees. They were AK-47s (and the stands came very much in handy as the butts of their rifles). They took these guns, lay down on the floor, and started crawling. The dwarves had to be evacuated immediately. Just as urgent was the need to reconsider my ideas about toys. About what “quality” toys are.

A toy is just a thing. It can be any thing. A child grants it the status of a toy and inserts it into his world of play—according to his psychological needs. I may be disgusted by toy monsters (and, frankly, I don’t get excited about playing with them), but children do need them for some reason. It may be that this is a way for them to make their fears material, giving them symbolic protection from an outer threat, or it could be channel for inner aggression, or maybe just something to feel bad for—it’s so ugly….

The same goes for books. Children read (or don’t read) for different reasons, they draw different morals from the books they read, and their preferences in books also differ. Does this mean that my criteria of “quality” are meaningless? No, it does not. They do have value for me personally. It’s natural that each of us unconsciously seeks out people that share our literary preferences. We say that these people are “kindred spirits.” We may have many such people, or very few. But no matter their number—our shared preferences in books are those of a set circle of people. They can’t apply to everyone.

A roundtable for publishers, writers and critics took place at the Krasnoyarsk Book Fair. They wanted to see if they could reach an understanding. Every participant said more or less the same thing: we want children to read quality books. Books written in a good literary language. At the same time, each participant believed that it is she who knew how “good literary language” should be defined and what a “quality book” was. There wasn’t a single writer—isn’t it strange?—who stood up and admitted to writing books in bad literary language.

What am I getting at here?

There is an incredible amount of books out there today. Which means basically every potential reader has his perfect book. And every book will find its reader. It is impossible to create a universal literature rating scale. Books are evaluated by various expert communities which exist around awards, sites, and clubs. Assessments by these different communities may not match. Furthermore, praise for a book within one community can serve as a marker with the opposite sign for you. That’s perfectly fine, provided there’s a choice.

The opportunity and ability to choose have become important characteristics in the modern young reader. It wasn’t always so. Nowadays, young parents don’t just say: “Let me read to you.” They ask: “What book would you like me to read you?” They ask two-year-olds and see that even they like having a say. Of course, a child chooses from a certain book “fund,” one that was previously assembled by the parents relying on their own standards of beauty. That’s great! Even so, it’s impossible to force a child to listen to a book she doesn’t like. So parents involuntarily create a library taking the child’s interests into account, because it’s important for them to make the child read. There is a complex interaction here.

I’ll reiterate: of course I want the children I interact with to share my book preferences. I try to tell them about the books in a way that captivates them. I try to read them what I like, in a way that will make them like it too. But I don’t have the right to insist that everyone has to read the books I see as “quality.” So it probably is better that someone read something than not read anything at all. This, too, is progress.

Marina Aromshtam

Translated from the Russian by Alisa Cherkasova

Cover image: flickr.com

Follow us on Facebook.