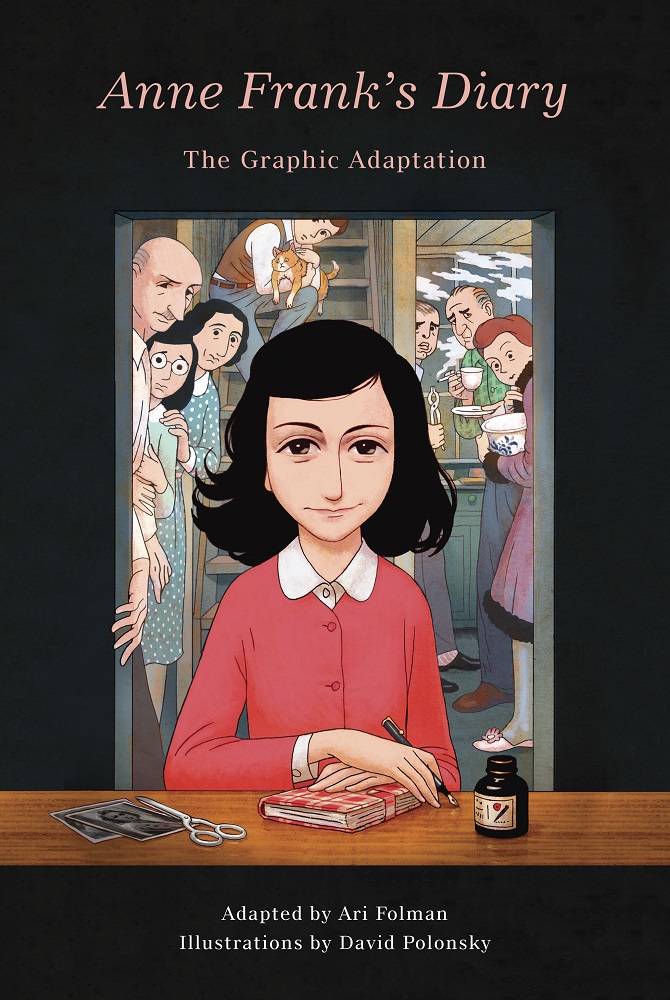

Anne Frank’s Diary, one of the most striking pieces of documentary evidence from the Holocaust, recently took on new life in the form of an eponymous graphic novel Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation is illustrated by David Polonsky, text is adapted by Ari Folman. The English edition will be published by Penguin Random House/Pantheon in October 2018. ISBN 9781101871799 . How will readers respond to this new work? Can pictures replace the original text? And how should we approach this new book in general? Papmambook’s teenage experts share their thoughts.

Maria Dorofeeva, 16

I think the publication of The Diary of Anne Frank as a graphic novel is an important event. I was amazed with the force of its stunning, deafening effect. In each picture, the reader hears Anna’s voice in the background, narrating events as in a movie. It’s significant that the graphic novel version of the Diary isn’t a new work, as film adaptations of books often are, but retains Anna’s voice, her caustic irony, strength of spirit, and sense of humor. That’s why I see this graphic novel as a translation of The Diary of Anne Frank into another language—the language of images—which has its particular means of affecting the reader. For example, Anne writes in her diary that the Nazis have forbidden Jews from going to the pool and have imposed a curfew. In the graphic novel we see Anne by a pool full of people, while Nazis order the Jews out of the water. Or we see Anne coming home from a date. Her father, worried that she must be home before the curfew for Jews, meets her at the door. Both that pool with people and the worried father waiting for her at the door help you to see the diary not just as documentary evidence of the past, but also as a story that touches you to this day.

Polina Zelenova, 16

Anne Frank could have grown up to be a great writer and write many wonderful books. But even her only work—a personal diary—affects readers not just because it recounts the true tragic story of the Holocaust, but also thanks to the indisputable literary value of the text. Anne’s conversations with Kitty (as she called her diary) are full of deep musings, irony, and rich description.

The creators of the graphic novel based on The Diary of Anne Frank were able to convey not only the terrible events and feel of that time, but also Anne’s lingering childishness, her irony.

Did Anne’s diary lose its documentary nature in the process? Of course not. But with the new format it is no longer just a diary, it becomes a creative work. The reader’s attention is drawn to the girl’s personality, her doubts and worries, which (except for those related to the war) are familiar to any child her age. So the whole story acquires a slightly different feel. The poignant conclusion, horrifying in its realism, returns us to starting point—first and foremost, this is a book about war.

As you close the book, you realize that Anne’s dream of becoming a writer and writing a book read by millions came true thanks to her father. When you think that, you can’t help but to also feel deep sadness and regret.

Eva Biryukova, 14

Until very recently I couldn’t quite imagine a graphic novel on a serious topic. To me, works of this genre were something like comic books. But Louis Undercover A novel by Fanny Britt, illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault. English edition: Groundwood Books, 2017. ISBN 1554988594 rocked that сonviction. For its part, the graphic interpretation of Anne Frank’s Diary convinced me that the synthesis of illustration and text is not for lazy readers, who can’t form their own visual images of characters. To the contrary, the fusion of image and text makes a strong impression. The ability to see what Anne is writing about, to see those she lives with and thinks about—it feels like a dialogue with the characters. It’s not reading but a conversation. At times it even felt like she was addressing me directly.

The pictures complete and strengthen Anne’s image. They convey her character, the irony of her relationships with her neighbors in the Annex, her ability to analyze, and the inner struggle brought about by adolescence, the war, and family relationships. I think the pictures bring Anne closer to the reader, make her easier to understand. I thought and read about her not as a Jewish girl hiding from Nazis, but simply as a girl my age, who had the same problems I, and many other teenagers, do. Her incongruity with those cruel times and her disagreement with her parents’ ideas about how she should be often bring Anne to despair and it’s then that I feel it’s not just Kitty she’s telling it all to—she’s also venting to me. I was awed by her strength of character and the wisdom in her introspection. I hope her ability to see good in the world around her helped her persevere to the end. I’m certain that to the very end, Anne didn’t let anyone break her spirit.

I didn’t find that this work lost any of the diary’s documentary nature or realism. I think this interesting format produces an even stronger emotional effect. The reader learns about many aspects of that historic reality, but at the same time Anne remains a regular girl and her personal tragedy takes the foreground over the tragedy of Nazism. I was amazed at her words that in youth one is more lonelier than in old age. Maybe, each of us, at any stage of life, is essentially impossible to fully understand.

Darya Ponomareva, 16

Many girls write diaries in childhood. They usually begin with “Dear Diary…,” followed by a few pages of text and then—nothing. An active child rarely has the desire or focus to make regular entries. Anne Frank, a Jewish girl living in Holland with her family, started writing on June 12, 1942, in the midst of World War II. The entries come to an abrupt end on August 1, 1944, when she and her loved ones were captured by German Nazis and sent to death camps. When the war ended, Anne Frank’s diary was published by her father, who survived, and translated into many other languages. It was first published in Russian in 1960. Now we have the opportunity to meet the new, graphic novel version of The Diary of Anne Frank, created by screenwriter Ari Folman and illustrator David Polonsky.

Books about war always make you feel a certain unrest. When you pick them up, you unwittingly hold your breath, as though trying not to disturb the memory of the dead. Often, you don’t want to touch these books at all—it can be too hard to think about the fact that there was such a terrible war and people were exterminated for their ethnicity. The Diary of Anne Frank, though, is a book you want to turn to again and again. It’s not just a monument to history; it’s the living, heartfelt story of a teenage girl.

Anne lived an absolutely ordinary life, which she described in her diary: conversations with peers, skating with her sister, resentment at her father who noticed his older daughter Margot to the neglect of Anne, arguments with her mother, who lacked tact…. The diary of this girl would have been no different from hundreds of other such notebooks, hidden from sight. Anne would have grown up, gotten married, bought a house and had kids, and her childhood diary would have gathered dust in the attic in a box that was never opened since the move. But the war changed everything.

As you leaf through the pages of the graphic novel, you are gradually sinking into the atmosphere of the Second World War. You read about the girl’s fears, her pain, her dreams of one day finding herself outside of the annex where her family must hide. Bright, everyday pictures give way to terrifying visions in thirteen-year-old Anne’s imagination. The style of these pictures is harsher, more grown-up.

The graphic novel format allows you to not just read but also see: gestures, colors, emotions…. I think this graphic style is the most fitting choice for Anne Frank’s diary. The artist was able to more fully develop Anne’s image—that of an ironic, self-critical, sensitive girl who found it hard to take the nitpicking from adults about her behavior. Though she lived surrounded by people, she was very lonely. Writing it all out in her diary allowed her to feel less neglected.

In reading this girl’s diary, you gain respect for her. It’s not every adult, not to speak of a child, that can survive a life “in the shadows.” Hiding in a secret annex means eating very simple food, not being able to talk loudly or see friends. When she got into fights with her parents or members of the other family that lived with them, she couldn’t just go outside to let off steam. The hurt got bottled up inside until she could pour it out in her diary through sharp, ironic remarks. The graphic novel allows the creators to illustrate that irony, as when Anne is depicted as a sharp-nosed, frowning bird and her mother as a praying sheep with a bell on its neck.

Much of Anne’s story is relevant to this day. Teenagers of the twenty-first century often experience the same emotions as Anne did seventy-five years ago. The comic book formal draws attention to ethnic intolerance, which oppresses our society. Reading Anne Frank’s diary allows you to see the problem from inside and be horrified at human cruelty.

Anna Semerikova, 12

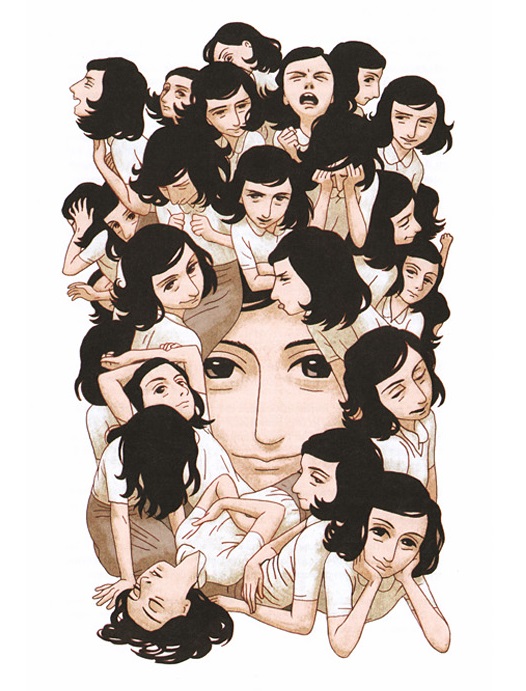

When I heard that a new comic book based on my beloved The Diary of Anne Frank had been released, I winced inwardly because I don’t like comics. Usually they consist of simple drawings and the text serves only as a caption to the drawings. I prefer big books with intricate plots. And the diary of a teenager is too serious a matter to turn into light reading. But this particular comic book ended up being much more exciting and sophisticated. For example, artist David Polonsky managed to portray Anne as a bright and emotional girl. One look at the collage of portraits expressing Anne’s emotional states is enough for the reader to immediately understand what was going on in her soul. Getting the same insight from Anne’s diary requires much more time and effort because the information is scattered throughout the text. One of my favorite illustrations is Anne falling in the abyss. In my opinion, it is hard to convey the loneliness of a teenager any more accurately. Or take, for example, a picture which is not about Anne's inner world but rather shows what was happening on the streets of her city: the gray mass of people with their arms raised in the Hitler salute. The reader can just feel how similar, obedient, and aggressive they are. With these discoveries, I set aside my previous prejudices and began to read the book more carefully.

Another surprise was waiting: the further the text of the graphic version unfolded, the more it looked like a real diary. Now it was not a primitive comic book but a fascinating graphic novel. When Anne tells the story of her first love, writes about her quarrels with adults or her expectation of the allies' landing and her rescue, the text has not been abridged. I sunk into it the same way as with Anne’s original diary, but now it was accompanied with the graphic representation of her state.

But the main thing that truly helped me come to terms with the graphic diary was the creative doubts of the project’s author, Ari Folman. I was surprised to find in the afterword that he had the same feelings as I did when I opened the book for the first time. He also thought it was impossible to make a comic book based on such a powerful book by just illustrating each page of it. It would have taken five years and several thousand pages. The author and the artist came up with an amazing compromise. They kept the essential events from the diary and replaced the words with drawings where it was possible to do so without losing the meaning. And they did all this clearly and vividly.

Of course, the comic book format might surprise you if you first read the classic version of Anne’s diary. But if you start with the comic book, you will definitely want to find the original. The same thing happens when you first watch a good film based on a famous book you’ve never read. You rush to the library because the movie scenes are still fresh in your mind’s eye. It’s just the same with the graphic version of Anne Frank’s diary.

Ksenia Barysheva, 14

“It sounds strange and somewhat disrespectful: Anne Frank’s life is set to become a musical.” This line is from an article about a musical production of “Anne Frank” in February 2008 at Madrid’s Calderon Theatre. The author considers whether the musical genre is suitable as a means of telling about the tragedy of the Holocaust. Ten years later, author Ari Folman and illustrator David Polonsky have created a graphic novel based on Anne Frank’s diary. So we’re faced with the same question: can we use comics to tell the story of gas chambers, cargo trains, and concentration camps? I personally think the issue is not the suitability of the genre. Rather, the questions are why the author chose to retell the story, whether he can convey the content of the diary in his own work, and what he wants to add to the original Diary.

There have been a number of works based on this historic document. Anne Frank’s diary was first made into a Broadway show and, in 1959, it became a movie. Directors and screenwriters consulted with Anne’s father, Otto Frank, who was the sole survivor among the Annex’s residents. The movie was filmed on a set with original items, but Anne’s story was transformed into a melodrama where a sweet Anne, batting her heavily made-up eyes, gets ready for a date with Peter in the attic. The film ended with Anne’s words: in spite everything, she still believes “people are really good at heart.”

The audience sees only one Anne in this movie—a life-affirming and witty one. But Anne was entirely different in real life. Her diary reveals a deep, strong personality. She was a rebel and unlike all the other family members, a person with an opinion she was not afraid to express. She was able to analyze her own struggles, as well as the events around her. Anne grows up rather quickly while in the Annex, but it’s not all down to circumstance—she was different from the very beginning, and that’s why her family had such a hard time understanding her.

The new, graphic version of the diary tells us of Anne, exaggerating her inherent sarcasm. At first glance, the sarcasm may seem impossible, excessive. You might find it repelling at points, until you understand that Anne’s sarcasm is her way of being. It is a defense mechanism against constant tension and the ever-present fear of being found, a way to avoid thinking about what is happening outside the walls of the Annex, and a defense against the constant nitpicking from other residents of the Annex, their misunderstanding. The door that hides the Annex’s residents from the outside world is too thin: at any moment someone could hear steps behind the wall and report them. Anne pushes those thoughts away, defends against them, trying to focus on the little things. But the fear comes to her when she has no control over it—in her sleep. The authors of the graphic novel find a very effective approach by showing Anne’s thoughts and fears about what is happening through her dreams. The fear catches up with her there, where she is defenseless. No sedatives or sleeping pills will help. After she takes a pill, Anne falls asleep, but the smell of crushed metal breaks through the perfume of field flowers and again she dreams of the Nazis’ advance….

In the graphic novel version, Anne laughingly tells about the way each resident of the Annex makes space to wash up. This is essentially the only time and place where each person can be alone for at least some time. Is it any wonder the residents of the Annex were so devoted to this ritual?

But Anne isn’t always sarcastic. With one phrase, she can convey her feelings and emotional turmoil. As they look through a thin crack in the dark, heavy curtains, Anne and Margot see two Jews walking down the street. People begin to part around them and the pair is led away by Nazis. Anne says she feels as though she has betrayed them and is now spying on their misfortune.

In the graphic novel, there’s one picture which very precisely conveys the girl’s feelings about the hundred days she’s spent in the secret annex. Anne spends her days with the same people who endlessly repeat the same stories and the picture around the girl depicts wind-up toys that cry out with the same phrases until they break.

Anne Frank’s diary reads nothing like a love story. Anne acknowledges that she drew Peter in only because it seemed he would be able to understand her. She needed someone with whom to share her thoughts, to be herself. But it all turned out differently and Anne was perfectly aware that Peter couldn’t support her. She felt lonely. Her diary, Kitty, remained her one true friend. In the diary, Anne speaks more harshly of her relationship with Peter than the graphic novel depicts. When she realizes that she can’t speak with him about what truly matters to her and what she feels, Anne asks if that is the way it always is. Is complete closeness and complete trust possible between people?

The last entry in Anne’s diary contains musings about herself. She says that as soon as she gets quiet and serious, people think she is acting some new role, and she has to extract herself from the situation by joking. I think this is the key to understanding the graphic novel version, where Anne hides her true feelings behind jokes. Her sarcasm is just a mask. Otto Frank thought he was able to build a little corner of heaven for his family in the Annex, while people were dying outside. But it was actually hell. And Anne understood that perfectly.

The graphic novel is much shorter than the original diary. Of course, it’s impossible to translate every word Anne wrote into an illustration. It’s very hard and likely impossible to illustrate Anne’s reflections about religion, about God.

When you read reviews for The Diary of Anne Frank, you often see young girls saying that they feel they are like Anne. They too fight with their parents and older sister, dream of their first love, worry about their emerging femininity…. The authors of the graphic novel emphasized Anne’s uniqueness and her individuality, the ways she differs from thousands of other adolescent girls. It’s impossible to identify with an Anne like that, but that is exactly what the graphic novel is about—about the death of a unique and talented girl, Anne Frank.

At first, the text was not published in full. Anne’s father, Otto Frank, took out some of Anne’s harsh words about the other residents in the Annex, as well as her thoughts about sex. Anne was certainly unlike other girls, but she never wanted to be like them. Her thoughts seemed too radical for her time.

It could be that in 1959, the scars of World War II had not yet healed, and so Anne Frank’s story in the film of that year was softened into a melodrama. Maybe people simply didn’t want to recall what had actually happened. Now that seventy-plus years have passed and there are few surviving witness of the war, it’s time to think anew about the events of that time. The graphic novel interpretation of the Diary is one such attempt.

Translated from the Russian by Alisa Cherkasova

Cover image: penguinrandomhouse.com

Follow us on Facebook.