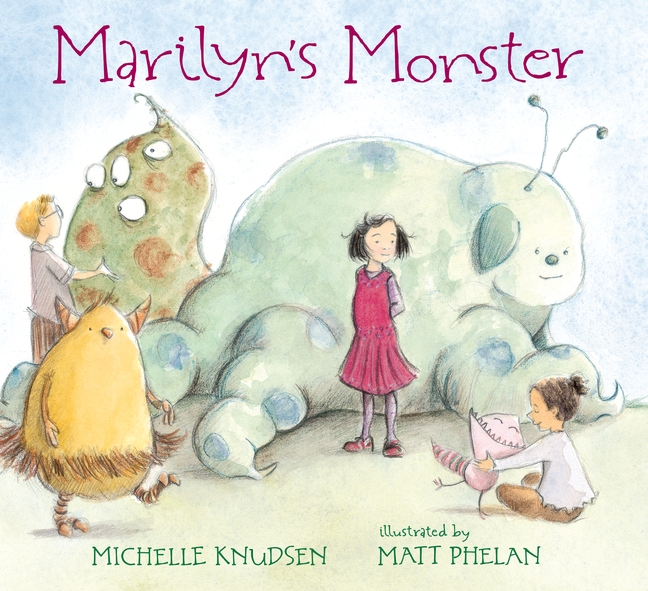

The title and cover of Marilyn’s Monster [most recent English edition: Candlewick Press, 2017. ISBN 9780763693015] will draw in a four- or five-year-old immediately. The cover teems with all kinds of creatures, monsters, and beasts. And it’s not just monsters on their own—it’s a mixed group of children and monsters. It’s a happy group—the kids are not only unafraid, but obviously good friends with the creatures around them.

Some parents might furrow their brows in disapproval. Here we go again, they think, children’s literature devoid of any values. To them, it won’t matter much what’s actually inside the book. It’s quite enough that the book is about monsters. It’s already repugnant. But kids would beg to differ.

Dinosaurs, dragons, transformers, and just plain monsters of any kind are an integral part of a modern children’s subculture. The fact that they’re not scary and that the stories around them focus on taming (rather than fighting) them are vital signs of our modernity.

Image: candlewick.com

After all, what do these monsters, who have taken over children’s literature, represent? It’s a legalization of that sphere of children’s lives which for many years adults wanted nothing to do with. It’s a symptom of how the idea of childhood has transformed from the one we had just a couple decades ago, sharing the misconceptions of 18th century thinkers who believed that a child was a blank slate. And a blank slate isn’t just “blank.” It’s flat, too. Another common metaphor for a child was wax, the idea being that we could mold what we wanted. Behind these good intentions was an obvious desire to manipulate. Is a child wax to be molded? And how far can we take our attitude of molding “all we want”?

If a child is neither wax nor blank slate, but a person that’s multi-dimensional and resistant to molding, then we have to get up the courage to deal with the monsters of the world of children.

This theme is developed consistently only in foreigh books we have in translation. There, it would appear we have no shortage of variations. There are books about children taming monsters that personify their fears. Books that teach us to laugh at those fears. Books where monsters live a “human” life, which allows the reader to “negotiate” with them.

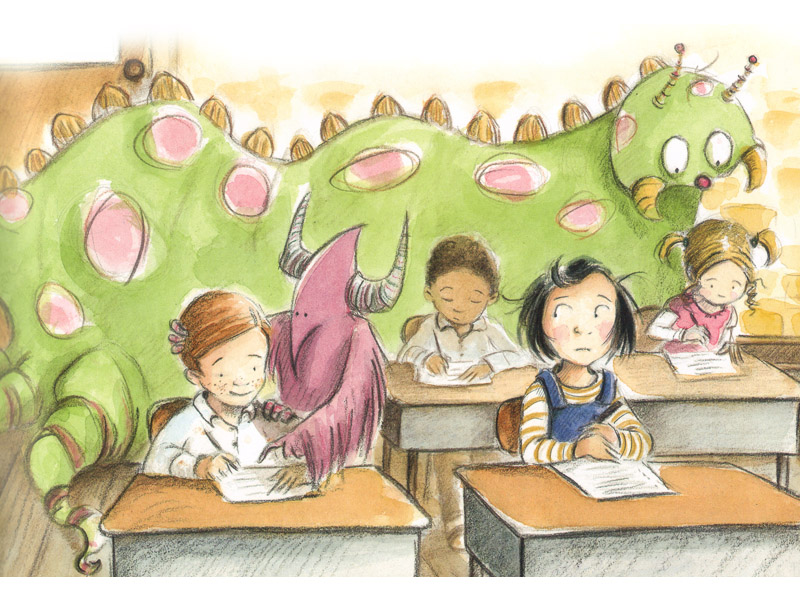

But the authors of a certain book about a girl named Marilyn overturn all our expectations. Here, the creatures fulfill some entirely different role. It turns out every child has their own monster. That is, every child should. A monster is a cross between a family pet, magic guardian, and playmate. All of the monsters are completely different, almost a reference to that well-known psychology test that asks you to draw an imaginary animal, revealing, in turn, a lot about the drawing’s author. Every monster is an integral part of the child herself, her second “I” made flesh and confidently taking up space, with magic powers of invincibility to boot. (At any rate, many monsters are quite “substantial” and have obvious defense mechanisms like fangs or claws.)

One has to “get” their monster, and once that happens, it’s your monster for good. When the monster will show up is generally unpredictable and is nearly always unexpected. Timmy’s monster first materializes during a history test, Franklin meets his at a library, Rebecca gets hers while riding a bike, and Lenny finds his when running from bullies. It might seem at first sight that monsters appear in very different situations, but that situation might have to do with looking deeper inside yourself or mustering up your courage. It’s a sort of personal revelation—you open your eyes one morning and there it is, your monster, right in front of you.

But for Marilyn, the protagonist of the book, nothing of the sort happens, and not having a monster of her own is a source of distress. For some reason, she can’t seem to make her individuality take form. She tries to be very good—and then very bad. But those are just “external attributes.” And so those outer efforts lead nowhere. In her case, trying to do what everyone does is a failure. Clearly, you need to do things not like others do them, but in the way you feel is right, or necessary. For that, you’ll need decisiveness and a sense of your own will. That’s the strategy that allows Marilyn to finally get her monster. She finds her own monster, rather than the other way around. Let her brother grumble (“that’s not the way it works.”) Marilyn now understands that “you don’t really know.” “Maybe,” she says, “my monster is different.”

There are no strict formulas which allow one to come to oneself, discover something important in oneself. A person (or child) has to find one’s own path every time.

Of course that metaphoric level and its logical analysis will elude a child of four, and even, quite likely, a child of seven. For a little reader, this is something of an “everyday story,” where curiously drawn monsters play with children as equals. And that’s very nearly the truth: just look how interesting life can be!

Actually, that is the truth—the way things work in life is absolutely fascinating!

Marina Aromshtam

Translated from the Russian by Alisa Cherkasova

Follow us on Facebook.