Gary D. Schmidt is a contemporary American author, honored with some of the most prestigious literary awards in his country. In a short space of time, he has earned himself avid fans among Russian readers. Of course, we wanted to ask him all sorts of questions: how autobiographical his books are, what he thinks it means to write for teenagers, and much more. Our dialogue with Gary Schmidt was a very interesting one.

- What does it mean for you—such a response to your novels in Russia?

- To have a good response to a book of mine in Russia is incredibly humbling. To have a book translated into the language of Dostoyevsky is humbling. And perhaps most gratifying of all is the idea that these characters and situations are somehow translatable, that they can reach across national and cultural boundaries and speak to young readers on either side of the globe. As a writer, you hope that a reader can be powerfully affected by your stories; to understand that this can happen around the world is amazing—it is something to be thankful for.

- How do you imagine your Russian readers? Do you think they are similar to American readers in terms of their age and interests?

- When I think of young readers in Russia, or here in the States, I envision the same kind of reader: their lives are, in the words of Richard Peck, "unfinished portraits." So much has begun for them; in so many ways, they are becoming their own person. They are moving out of childhood, and into adulthood—with all that adulthood means. They are finding ways to understand and articulate their most profound hopes and dreams, and beginning to look for ways to make those happen—even daring to believe that they can happen. They are living lives that are suddenly changing, in bodies that are suddenly changing, and trying to find ways to juggle and intermix all the lives that they are leading simultaneously. They want to be taken seriously. They want to have a voice. I think these things are true for all young people around the globe.

- You know, after reading your book my colleagues and I were sure that you were much older and your novel is a classic of the 20th century. It is so amazing that you have written it not long ago. Is this novel based on your own experience?

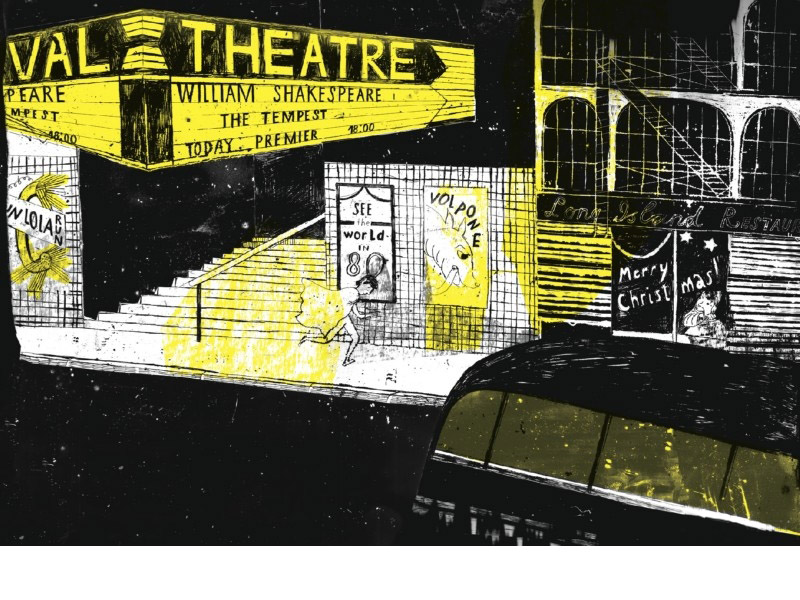

- Is the novel based on my own experience? Sort of. The events of The Wednesday Wars are all based on real experience, most of it mine. But, those experiences are then heightened and exaggerated. We did have gerbils and even a snake that escaped, but they never did re-appear like the rats. I did have a horrible experience on the stage, but it wasn't in a Shakespearean drama. And so on.

In Okay for Now, I wanted to write about a kiddo whose life was much more beat up than mine had been—the kind of kid I had known growing up, who always seemed on the edge of trouble and disaster. Only when I got older did I understand that this was not his fault, and that the proper response would have been compassion. I wanted to try to understand Doug, who has so little, and who wants at least one stupid thing to be perfect in his life. It doesn't seem like a lot to want—but we can never get it.

- Does the main character have any of your features when you were a child?

- Holling is about as close as I will ever get to autobiography. Doug, too, has qualities that are mine, particularly his difficulty reading when he was young. But it is Holling who is closer, with his desire to be taken at his word, his desire to grow up and have a voice, his hope for love, his surprising sense that art can really speak to him.

- You mention Holling’s "sense that art can really speak to him." Do you think that has something to do with Shakespeare? Do you think it is because he was reading Shakespeare?

And a related question: did you read (and like) Shakespeare when you were a teenager?

- On art speaking to Holling: "Speaking" is a metaphor, obviously, but it does seem to me that certainly one role of art is to engage us, to give us more to be human beings with. There are reasons that terrorists destroy art, and the rest of us read, or go to plays and museums, or make pottery, or take photographs. Art should be showing us more about the world, about our lives, about the lives of others. As a writer, this is what you hope for—not that a book should ever make pronouncements, but it should, even as it tells a story, point to something more.

Does Shakespeare do this for Holling? Yes. It did for me, too, when I read the plays in middle and high school. Does Shakespeare do this for everyone? No. That's one of the miracles of literature. There is this huge, huge table that has been set with so very much, and different folks will enjoy different dishes. A young reader is just discovering this, and one of the breakthrough moments for any reader is the knowledge that he or she doesn't have to love everything. And to be aware that tastes will change; I read The Scarlet Letter over and over these days.

- Do you think it is necessary to read classic literature in childhood?

- Should every young reader read the classics? No. I was forced to as a young reader, and hated them. The Scarlet Letter, David Copperfield, Great Expectations. I couldn't stand them when I was forced to read them. But, it is another thing to be invited into the classics, where force was not an issue. I read Dante after I read Tolkien, and loved his poetry. But if I had had to read him . . .

Today, I think we have wisely come to recognize that many of the classics that we have forced upon young readers were never meant to be for young readers. Walden is meant for "poor students," but Thoreau was talking about college kids. Melville never imagined Moby-Dick in the hands of a middle school kid, though Dickens did imagine his work being read aloud to children—though reading something aloud changes the dynamics, doesn't it? I think that that opens us up to new works that are aimed at the middle school and high school experience, and this makes it an exciting time in writing books for young readers.

- Your understanding of adolescence is great. But there are some cruel episodes in your novel where Holling and Doug encounter teenage cruelty. Is cruelty a common feature of this age or a feature of life in general?

- I want to be honest when I write; I don't want to sugarcoat a world that is so very broken as our own is. To tell a kiddo that everything is going fine, or that there's a silver lining, or that he's going to grow from this experience, can sometimes—perhaps even often—be a lie. The world is broken, and the world can be cruel, and I think we need to acknowledge that in our writing for middle and high school students. Since they will find great cruelty in their own lives, I don't think we should hide it, but examine it, and try to understand it, and do what we can to remedy it in very specific and concrete ways. Cruelty needs to be withstood on a global scale, but also in the hallway of a school, in a locker room, in an office, in a home. So I do want to be honest, and to show stories where there is cruelty—but I don't want to take away hope. I want all the stories to show resilience and strength—though it may not be the kind of strength we all imagine. Perhaps a spiritual strength, would be how I would put it.

- Do you think that every person has to come through such experience? Is it necessary?

- Is it necessary to come through an episode of cruelty? No. But I think it is inevitable.

- Is the topic of the Vietnam War relevant for American society now? What does it mean for modern teenagers? Is it just history or something else?

- Vietnam is incredibly relevant to today's teenagers. Both Russia and the U.S. have had long, protracted wars that seemed to have no way of ending—which was exactly what the Vietnam War was. I wonder if either nation has learned the senselessness of imposing will through military power: history is so clear that this cannot work, but we do it anyway.

- What do you tell your students when they ask you what makes a good book? What is good writing for you?

- What makes a good book? First, story. Second, story. Third, story. No young reader is going to push through a book that he or she feels is really talking behind his back. The writer, as E. M. Forster asserts, has to first make the reader want to turn the page. Anything else is an afterthought.

- In general, what were some of your favorite books when you were a child?

- When I was a kiddo, my favorite books included the My Bookhouse series, a set of six books put out in the 1920s and 1930s, mostly with European stories and folktales. I also read the Homer Price books, the Herbert Reed books, the Freddy the Pig books, the Doctor Dolittle books—all those that tended to verge on fantasy. Later, H. G. Wells and Jules Verne and then Ray Bradbury, the greatest science fiction writer of them all.

- In your opinion, who are significant children’s authors today?

- Start with Jack Gantos, and M. T. Anderson, and Ron Koertge, and Gene Luen Yang in graphic novels, and E. Lockhart for young adult, Katherine Applegate, Kimberly Willis Holt, Nikki Grimes for poetry, Walter Dean Myers—who has now passed on but whose books will live—Mathalia Perkins, Pam Munoz Ryan, Lisa Yee, Linda Urban, Andrew Clements, Jacqueline Woodson, Matt de la Pena, Amy Timberlake, and on and on . . .it really is a golden age in this field. It's exciting to be a part of it!

In conversation with Maria Boston

Translated from the Russian by Alisa Cherkasova

Read a teenager's review of The Wednesday Wars here.

Follow us on Facebook.